In a recent post, I discussed heroes and anti-heroes in spy movies and westerns. This is the followup post I promised, but I’m going to leave the realm of popular heroes – those of fiction, entertainment, sports, and all who wear masks and tights. I’m going to discuss the heroes of myth, especially the “monomyth” as Joseph Campbell summarized it in The Hero With a Thousand Faces:

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

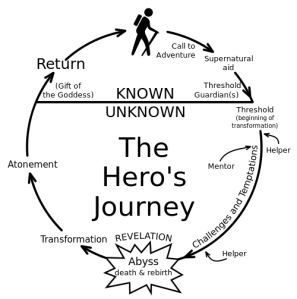

Here is a graphic that makes the elements of this type of story clearer:

I can’t think of heroes without remembering James Hillman, (1926-2011), the father of archetypal psychology and one of the most creative thinkers of our time. The two differing views of the mythic hero announced in the title of this post are Hillman’s own. He never shied away from ambiguity; “I don’t have answers, I have questions,” he said.

Hillman often railed at the negative effects he saw flowing from the hero archetype, which he saw as ego enshrined as narrow self-interest, both individually and collectively. For Hillman, the “heroic ego” was often a source of evil and mischief. Noting that heroes slay dragons, and earlier generations of Jungians wrote of dragons as “the mother,” Hillman claimed that heroes like Hercules in Greek mythology were emblematic of the modern world’s subjugation of women, “the feminine,” and “mother nature.” On another occasion he said, “Killing the dragon in the hero myth is nothing less than killing the imagination.”

Yet a recently published collection of Hillman’s work (Mythic Figures, 2012) includes a chapter on Joseph Campbell, compiled from talks he gave in 2004 in which he spoke at length of the positive hero. He put his earlier negative comments in context:

“A mistake in my attacks on the hero has been to locate this archetypal figure within our secular history after the gods had all been banished. When the gods have fled or were declared dead, the hero serves only the secular ego. The force that prompts action, kills dragons, and leads progress becomes the Western ‘strong ego’ – capitalist entrepreneur, colonial ruler, property developer, a tough guy with heroic ambitions on the road to success.”

When Hillman used terms like “soul” and “the gods,” his concern was religious, but not in the way of the literal truths of most organized religions. For Hillman, such literalism was the enemy of soul. He spoke only and always of the truth of the psyche because it precedes every other kind of truth: “Every notion in our minds, each perception of the world and sensation in ourselves must go through a psychic organization in order to ‘happen’ at all.” (Revisioning Psychology, 1977).

This understanding of the true hero in service to a Power greater ego prompted Hillman to revise his understanding of the “Father/Dragon/Ogre/King” the hero slays:

“A civilization requires the Ogre to be slain. Who is the Ogre? The reactionary aspect of the senex who promotes fear, poverty, and imprisonment; who tempts the young and devours them to increase his own importance. The Ogre is the paranoid King who must have an enemy. He is the deceitful, suspicious, illegitimate King whose Nobles of the Court [have] committed themselves to the enclosed asylum of security where they nourish their world-devouring megalomania.”

I think we know what he meant in 2004 by speaking of “paranoid kings” whose nobles live in “the enclosed asylum of security.” It has only gotten worse. How desperate the Ogre is to quash any budding heroes was revealed in a piece on August 19 on Time.com, “School Has Become too Hostile to Boys,” by Christina Hoff Summers. Three seven year old boys, in Virginia, Maryland, and Colorado, were recently suspended from school for the following acts:

- Using a pencil to “shoot” a “bad guy.”

- Nibbling a pop-tart into the shape of a gun.

- Throwing an imaginary hand grenade at “bad guys” in order to “save the world.”

The rationale for these suspensions were “zero tolerance for firearms” policies. Punishing pop-tart weapons in a culture that went on a gun buying binge in the wake of the Sandy Hook shootings seems too ludicrous to believe unless you see it from Hillman’s perspective – another step in the dragon’s war on imagination, in this case, the male imagination, the perspective from which most of our current hero myths derive. Along with banning snack food guns, such schools have renamed “tug of war” games as “tug of peace,” and halted dodge ball as too violent.

Fortunately, as Christina Hoff notes, such efforts to “re-engineer imagination” are doomed to fail – all they will do is “send a clear and unmistakable message to millions of schoolboys: You are not welcome in school.”

In We’ve Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy and the World is Getting Worse, 1993, Hillman made clear his belief that pathology lies in cultures as well as individuals, and we deprive the world of something when we take our rage and our grief exclusively to the therapist. Hillman never shied away from critiques of the world at large. Depression is “an appropriate response” to the world we live in, he said.

Yet stronger than the Ogre, said Hillman, is the myth of the Hero – not this or that particular hero, but the heroic pattern itself that Joseph Campbell restored for our times, which renews culture “by revivifying the archetypal imagination displayed by peoples the world over…The panoply of materials that Campbell catalogued shows that the hero wears a thousand faces and cannot be reduced to the modern ego. Especially important in recognizing him is recognizing the heroic liberating function of myth – that it speaks truth to power, even the Ogre’s power.”

We know from history and the nightly news how much suffering the decay of empires involve as paranoid kings strive desperately to hold on to power. We also have the examples of James Hillman and Joseph Campbell, who spent their lives pointing toward soul, psyche, and the language of myth and imagination. That is where we must look to find the larger truth – the hero brings the gift of renewal as surely as spring returns after the darkest time of the year.

I love how Hillman, with the eyes of a hawk, as if zooming in from afar, could get to the essence of our humanness, and that psyche is primary, nothing known or sensed comes to us except though the facility of psyche. As you note here: ” He spoke only and always of the truth of the psyche because it precedes every other kind of truth: “Every notion in our minds, each perception of the world and sensation in ourselves must go through a psychic organization in order to ‘happen’ at all.”

As well, Hillman’s ability to correct, revise, re-imagine, I think, comes from understanding that the nature of knowing always involves psyche, the images and gods of our human experience.

Love, love, love your post and am really enjoying reading your blog.

Debra

LikeLike

Hillman’s thought seems to me like the images in a dream – some of his ideas are unforgettable and yet impossible to pin down and turn into something concrete. Thanks for the blog complement – the appreciation is mutual.

LikeLike

You’re welcome! 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: 5 Reasons Why Breaking Bad is Macbeth | Writing Is Hard Work

Just catching up on my reading here. This is fascinating stuff, as usual for your posts, but the line that jumped out to me was “all they will do is ‘send a clear and unmistakable message to millions of schoolboys: You are not welcome in school.'” So many things happening around us, particularly in schools, seem designed to kill imagination and shut down the joy of being a child. I do think examination of the hero cycle is a great exercise for kids. I used to teach it in all my classes and think it gave kids a chance to examine their own lives and see the hero that lurks inside each of us.

LikeLike

You’ve mentioned teaching the hero story in school, and what a great ideal that is to pass along. It’s my impression, as I think it was Campbell’s, that the heroic imagination is something that arises spontaneously in young people. It’s tragic that so many institutions try to suppress it.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Psychopedia.

LikeLike

Excellent piece. I have often found the Hero’s Journey to be intensely fascinating. It is one of those rare theories that once you learn it, you find connections to it everywhere whether it be in popular culture, or even religions.

LikeLike

Pingback: Two views of the hero myth | Image of the World...

Reblogged this on Yoga Firsthand and commented:

I reblogged the first one. This the second: one correction though – I said that the Hero is an archetype – but really I meant to say that it is an archetypal journey through which the “hero” of the “story” passes through a version of the myth: the king, magician, prince, lover / queen, priestess, lover – etc. The “hero” in these cases is simply the person around whom the story revolves – It really has nothing to do with doing ‘good’ or ‘bad’. These posts, I imagine are not about the hero’s doing but rather the attitude with which they do it… Did I understand correctly?

LikeLike

Thanks for reblogging this. Yours is a perfectly valid way of understanding the hero story. I don’t believe for a minute that there is only one way. We owe a huge debt of gratitude to Jung and Campbell for recognizing and writing about this pattern. Distressing, uncanny, and terrifying experiences are a lot easier to deal with if they fit into a story. I was talking to a friend about Black Elk Speaks last week, and his story comes to mind now – Black Elk’s distress as he reached adolescence, and his good fortune in finding a Medicine Man who understood the consequences of “refusing the call.” Black Elk said he would have died if he’d continued on that course – though (fortunately) few of us have crises that severe, we do have crises, and people like Campbell serve as wise elders. A good thing, since few of us have access to wise village shamans these days!

That said, I think we all need to reimagine the hero and heroism for these times. I know I will have more posts on the subject and I look forward to reading what you have to say on the subject too.

LikeLike

I have never heard the story of the Black Elk – I’ll look it up. I have perused Joseph Campbell’s work and I may have missed it.

You have inspired me to want to write about this – from my own experience and I will endeavor to do so. I really enjoyed your posts and look forward to reading more.

Peace!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on ECAupgrade.com and commented:

Wow. I’m blown away by this post.

LikeLike

Pingback: What if our history and the myths and legions were wrong? | jaredtompson

Pingback: A Herculean Ego Rampant | tomkoontz

Pingback: “Wild”: The Unwilling Hiking Hero | Theresa's ENG4U Blog