I want to argue a paradox…that the origins, liveliness, and durability of cultures require that there be space for figures whose function is to uncover and disrupt the very things that cultures are based on. – Lewis Hyde

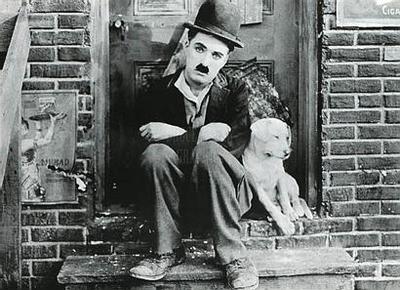

It has always made sense to me that the 1920s, 30s and 40s, when times were hard for so many, gave birth to our great movie tricksters: Charlie Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy, The Marx Brothers, and The Three Stooges. Their send ups of the 1%, among other things, are still hilarious. Where are their equivalents today?

My self-imposed moratorium on negative blog themes has passed. As I caught up on news I had kept at arms length, I found myself thinking often of trickster stories. In part because they are funny, and most of the news is not. And partly because the folly of tricksters has a sacred dimension while the folly of our headline makers is often just foolish. If you invite the Three Stooges to lunch and serve pie, the outcome is fairly certain. I read that the Georgia legislature voted to allow patrons to carry guns into bars; the result is likely to be just as predictable, but without the catharsis of laughter.

In his introduction to Trickster Makes This World (1998), Lewis Hyde emphasized several key points:

1) Tricksters both make and violate boundaries and live in relationship to them. Where there are no boundaries, trickster creates them, as in several Native American creation myths where Coyote makes the land and separates it from the sea. Where there are cultural boundaries, tricksters blur or invert the distinctions: right and wrong, friend or foe, male or female, living or dead.

2) Tricksters are usually on the road, and this makes them outsiders.

Through most of human history, solitary travelers have been rare. Until the last century, most people lived and died close to the area where they were born. Nomadic people travelled as tribes or clans, but Hyde says trickster is “the spirit of the doorway leading out, and of the crossroad at the edge of town. He is the spirit of the road of dusk,” who may pass through city and town but only to “enliven it with his mischief.”

Hyde points out that although there is an abundance of clever women who know how to be deceptive in world mythology, they are seldom full-time tricksters. Once the evil is vanquished, the curse lifted, they tend to settle down. Coyote and Loki do not domesticate, and the older cultures who gave us these stories would have had trouble imagining a woman who opted for a solo life on the road.

3) Tricksters are liars and thieves, but they are not petty criminals.

Tricksters steal things like fire and cattle, and according to Hyde, are often honored as creators of civilization. “They are imagined not only to have stolen certain essential goods from heaven and given them to the race but to have gone on and helped shape this world so as to make it a hospitable place for human life.”

We cannot be too doctrinaire about these things, for there is a distinction between “large” stories, like creation myths, and “small” folktales, where trickster sometimes steals cattle for himself. When he does so, however, in tales like “The Little Peasant” from Grimm, it is usually a case of swindling a swindler, or people who are dishonest and greedy to start with.

For obvious reasons, trickster isn’t welcome in corporate boardrooms. Like Robin Hood, he is into redistribution of wealth. He’s the patron of whistle blowers everywhere, and will gladly gum up the machine when it is no longer serving the greater good.

Perhaps that is why we need him now more than ever. We don’t even have to do anything. Hermes travels as fast as thought. For good and for ill, trickster is already here.

It’s odd that, given changing social climates, there aren’t many obvious female tricksters. There are the occasional stand-up comics who by commenting on social mores and conventions fulfill that trickster role that court jesters did. And then there are the journalist tricksters whose commentary columns point out societies collective inadequacies.

LikeLike

Of the several reasons Hyde proposes, the fact that the mythologies we have predominantly come from patriarchal societies is one of them. Yet he cites a few cases, like the Hopi and Tewa indians, with matrilineal cultures and women owning the land, where there is a female Coyote, but she is not as outrageous as her male counterpart in the same tribe’s stories.

It may be a matter of definition too – classical tricksters versus the kinds of deception in folktales, single episodes where you do not see beginning and after.

And it seems very hard now to see our emerging myths – perhaps it has always been that way – a culture’s living myths disguised as “reality.” What is sometimes sad is that Fox, Coyote, Raven, B’rer Rabbit, Anansi, will not be part of future stories since we live so far from the animal nations.

Hyde does suggest that trickster myths come from older hunting societies, since one of the driving imperatives is appetite – Coyote is hungry, and in trying to fill his belly he gets into all kinds of trouble.

LikeLike

Yes, that all makes sense to me.

LikeLike

Have been racking brains for female tricksters in mythology. Mostly it’s sirens, fays in disguise, crones and witches. But what about the Greek very rude little woman Baubo http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baubo She is most ambiguous biologically speaking, and apparently told risqué jokes to Demeter when she was downcast in her search for Persephone. I think she belongs to the earlier Persephone stories – ie those which Clarissa Pinkola Estes calls the Pre-Hellenic non-patriarchal stories.

LikeLike

I’ve heard the name, but I do not know the story of Baubo.

One thing strikes me now about tricksters – the difference between mythologies (like creation myths and other origin tales) and simpler folktales, which contain single episodes. It is quite possible that if we examined folklore or fairytale cycles like Grimm or The Arabian Nights, forgetting what we know of the larger mythologies (Hermes on Olympus) that we’d find a greater mix of the genders in the trickster area.

And the “simpler” tales are by no means less important. I always think of Marie-Louise Von Franz, Jung’s closest associate, who claimed that folktales are a much better window into the collective psyche than myth, since the latter have been elaborated by those with literary/philosophical/theological sophistication, while the “marchen” are closer to the unconscious.

Finally, a book was mentioned in one other comment – “tannin’s the female trickster.” I am not familiar with it but it sounds like it could be an interesting source.

LikeLike

What would you say makes the trickster trope?

LikeLike

My last few posts and some of the comments they’ve sparked have left me with more questions than answers. Is it valid to talk about animal trickster cycles, which may well date back to hunter-gatherer times, in the same breath as The Stooges? What about single episodes, like individual tales in The Brothers Grimm? I kind of think so – I guess the best I can do at this moment is say I can’t define trickster, just “know it when I see it.” Besides, if I tried to “define trickster,” I’m sure Coyote would eat my homework, or pee on it.

One thing I am wondering about along gender lines has to do with the “smaller” tales. I remember, for instance, a Grimm’s story about a peasant who takes shelter from a storm in a mill. Pretending to be asleep, he spies the miller’s wife having a tryst with the local parson. He uses that knowledge to get a fine meal,a warm bed, and later gets the parson to save his life. That reminds me, however, of a woman in an Arabian Nights tale, who gets the goods on four different philandering men of “official stature,” like a magistrate, a government minister, etc. Why we don’t think of both of those as trickster tales is a very good question.

LikeLike

Have you read tannen’s the female trickster, she poses some interesting notions on these elusive aspects

LikeLike

I have not, but I know several others who left comments recently will be interested. Thanks for mentioning this source.

LikeLike