“I cross the Green Mountain

I sit by the stream

Heaven blazing in my head

I dreamed a monstrous dream

Something came up

Out of the sea

Swept through the land of

The rich and the free” – Bob Dylan

Tag Archives: Culture

Hell or High Water: a movie review

Ben Foster and Chris Pine in “Hell or High Water’

Hell or High Water came out last summer. It ran only briefly in one local theater, so I finally caught it on iTunes yesterday. I’d planed to see it since reading an editorial that claimed Hell or High Water captured the mood of the country – at least the country between the coasts – better than any of the volumes of election year analyses.

Watching it, I remembered another great movie of hard times, Tender Mercies, 1983, but that was a film of redemption. There’s no redemption in Hell or High Water, just dry laughter at desperate measures aimed at overcoming desperate circumstance. “There’ll be no peace,” Jeff Bridges tells Pine in the closing scene. “This will haunt you all the rest of your days. And me too.”

Two brothers, Toby (Chris Pine), a divorced father, and Tanner (Ben Foster), an ex-convict, begin robbing branches of the Texas Midland Bank. Their mother died owing the bank $32,000 and back taxes after taking out a reverse-mortgage to save her failing cattle ranch. When oil is discovered on the land, the bank issues a foreclosure notice. Toby and Tanner set out to steal money from the bank to redeem the mortgage it holds.

The robberies are too small to interest the FBI, so Texas Rangers, Marcus (Jeff Bridges) and Alberto (Gil Birmingham) are assigned to the case. On the trail of the brothers, Alberto tells Marcus, “A hundred and fifty years ago, your great grandparents stole this country from my people. Now the banks are stealing it from you.”

Alberto’s ambivalence is mirrored by other people the rangers and the brothers encounter on their way to the inevitable showdown. Toby leaves a cafe waitress a $200 tip with stolen money. When the rangers arrive and demand the bills to check for fingerprints, the waitress says, “Get a damn warrant. This is half of a month’s mortgage. All I care about is keeping a roof over my daughter’s head.”

This is a country where hope for anything more than survival is missing. Thirty years ago, Tender Mercies showed Robert Duvall’s redemption from alchohol through the power of love and faith. In Hell or High Water, the only love is fast sex after a winning night at an Indian casino. The only reference to faith is Bridges’ comments on a TV evangelist – “He wouldn’t know God if God crawled up his pant leg and bit his pecker.”

Hell or High Water is not a depressing movie; it’s a sad movie. There’s a difference. The lonesome beauty of the land mirrors the towns that are falling apart, while the soundtrack, with songs from artists like Townes Van Zandt and Ray Wiley Hubbard, echoes the mood. Bridges’ world weary humor, and the brothers’ awareness of the irony of robbing the bank to pay the bank give us humor and moments of laughter even as a darker story unfolds.

Movies set in rural Texas have long depicted dying towns and troubled times. Think of The Last Picture Show, 1971, or No Country for Old Men, 2007. This one is filled with more topical references than any of the others. In one scene, the rangers stop as a couple of cowboys drive a small herd of cattle across the blacktop, fleeing a prairie fire that paints the sky an ugly black behind them. “It’s the 21st century,” one of the cowboys tells Bridges, “No wonder my kid doesn’t wanna do this shit!”

I’m not sure a single a single political pundit has captured as accurately the reasons this country voted the way it did in the recent election. At the same time, there’s a power in this movie I think will endure beyond any socio-economic circumstance. As Jeff Bridges character puts it, I think it will haunt the viewer for a long time.

Timely quotes from Reinhold Niebuhr

Reinhold Niebuhr (1892-1971) was an American theologian, ethicist, commentator on politics, and professor at Union Theological Seminary for 30 years. Among his most acclaimed books are, Moral Man and Immoral Society, and The Nature and Destiny of Man, which Modern Library named as one of the 20 best nonfiction books of the 20th century.

Neibuhr’s best known work, however, is the Serenity Prayer: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

In the wake of this year’s election cycle, his musings on history and politics have a special poignancy and relevance:

“The tendency to claim God as an ally for our partisan value and ends is the source of all religious fanaticism.”

“Frantic orthodoxy is never rooted in faith but in doubt. It is when we are unsure that we are doubly sure. ”

“Religion, declares the modern man, is consciousness of our highest social values. Nothing could be further from the truth. True religion is a profound uneasiness about our highest social values.”

“Religion is so frequently a source of confusion in political life, and so frequently dangerous to democracy, precisely because it introduces absolutes into the realm of relative values.”

Neibuhr’s most haunting observation to me is this, which implies that not a single one of the countless empires that have risen and fallen before ours made much of their greatness until it was gone:

“One of the most pathetic aspects of human history is that every civilization expresses itself most pretentiously, compounds its partial and universal values most convincingly, and claims immortality for its finite existence at the very moment when the decay which leads to death has already begun.”

Harbor Scene with Roman Ruins, Leonardo Coccorante (1680-1750), public domain

Irreplaceable

Leonard Cohen 1934-2016. CC-BY-SA-2.0

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.

– from “Anthem” by Leonard Cohen

Those who know Leonard Cohen’s poetry, music, novels, and songs, know he is irreplaceable. Those who don’t know his work actually do, for unless you were raised by wolves, you’ve enjoyed some version of “Hallelujah,” which I understand has passed “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” as the most widely covered song of all time. Both awaken something within us to hope in a dark time.

“Hallelujah,” written in 1984, was initially rejected by a recording company as not commercial enough. A Jeff Buckley cover ten years later brought it public attention, and since then, at least 200 artists have recorded their own versions, though to hear most of the 30 verses, you have to find Leonard’s version on youTube.

I first became aware of Leonard Cohen’s music through Judy Collin’s stunning cover of “Suzanne,” almost 50 years ago. It was covers, rather than his own gravelly voice that won him initial acclaim, though I remember vividly how his renditions of “The Stranger Song,” and “Sisters of Mercy,” were perfect for the moody western, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, 1971. “He was just some Joseph looking for a manger,” Cohen sings in the opening scene, as Warren Beaty, a hapless gambler, rides into a forsaken mining town under a lowering sky. That’s one of those lines that has stayed with me ever since.

I don’t really have a single favorite Leonard Cohen song – so many of them are memorable. What comes to mind this morning, and is best heard Cohen’s own voice, is “Joan of Arc,” another ballad that awakens hope in some deep, visceral way as it paints the portrait of time of darkness and suffering. It still sends chills down my spine.

I send this post out to Leonard in memory of a debt of gratitude that can only be repaid as we seek for something deeper and brighter behind the apparent disasters of our lives.

My Fulfillment Package

The voice on a recent robo-call, in the masculine-but-chirpy tone of a game show host, said, “Hi, this is Tod, here to tell you your fulfillment package is ready! Having just come from the meditation room, I wondered what kind of fulfillment Tod was selling. “Stay on the line for details on how to get your medical alert package.” I hung up.

We all know Big Data is watching our every keystroke, and that “secure information” is an oxymoron, but although “they” may have accurately placed me in the medical alert demographic, they don’t understand my idea of fulfillment. Or do they?

Every “positive psychology” poll I’ve ever seen on the key factors of happiness lists “good health” as most important, so perhaps Tod wasn’t that far off. Or so you might think, unless you’d seen the third annual Chapman University Survey of American Fears, which lists the flip-side of happiness, things that get in the way of fulfillment. The top fear, listed by 60.5% of the 1511 Americans surveyed was, “Corruption of government officials.”

Understandable, especially this year, but it also tells me that the survey is skewed toward a young demographic. Trust me, when you get old enough to care for a parent with Alzheimer’s, the things you fear change dramatically. Plus, I’m cynical enough to believe that “corrupt government official” is usually redundant – like speaking of “wealthy millionaires.” (There are 383 of those in Congress, by the way).

Here are the results of the survey:

- Corruption of government officials (same top fear as 2015) — 60.6%

- Terrorist attacks — 41%

- Not having enough money for the future — 39.9%

- Being a victim of terror — 38.5%

- Government restrictions on firearms and ammunition — 38.5%

- People I love dying — 38.1%

- Economic or financial collapse — 37.5%

- Identity theft — 37.1%

- People I love becoming seriously ill — 35.9%

- The Affordable Health Care Act/”Obamacare” — 35.5%

Interesting to note that by a small percentage, more of us fear losing our guns than losing our loved ones. Nope, not my fulfillment package.

However, fear of clowns didn’t make the top ten, so perhaps we can let Stephen King off the hook….

Of cutting trees and the truths we cannot handle

George Washington and the cherry tree

The story goes that George Washington received a hatchet for his sixth birthday. With it, he damaged a cherry tree. When his father confronted him, young George said, “I cannot tell a lie. I cut it with my hatchet.” His father embraced him and said, “Your honesty is worth a thousand trees.”

Ironically, this paean to honesty was the fabrication of Mason Weems, an itinerant preacher and one of Washington’s first biographers (the cherry tree myth). Politically expedient falsehood has been with us from the dawn of our Republic.

Readers of theFirstGates and movie buffs will recognize the other part of this post’s title as a partial paraphrase of the Jack Nicholson line, “You can’t handle the truth,” in A Few Good Men, 1992, which I referenced through a link on August 8.

It came to mind last night as I watched Nixon, the third PBS documentary on American presidents I’ve seen this week. It’s a fascinating series for those interested in history, and especially during this disheartening election year. The truth I find hardest to handle is that even the pretense of truth has become optional during elections.

After his discharge from the navy after WWII, Richard Nixon ran for congress against five-term Democratic representative, Jerry Voorhis. Nixon won 60% of the vote, after, among other things, spreading the word, via anonymous telephone calls, that Voorhis was a communist.

“Of course I knew Jerry Voorhis wasn’t a communist,” Nixon later confided to a Voorhis aide. “But I had to win. The important thing is to win.” I was actually happy to learn that the lies that permeate this campaign are not a new aberration, but more a case of deja vu all over again. The only difference is that in earlier times, people caught in blatant lies were certain to lose – the appearance of honesty was a matter of style and decorum.

Political lies cross party lines, of course. Feeling compelled to be as “tough on communism” as Barry Goldwater in the 1964 election, Lyndon Johnson engineered the Gulf of Tonkin “incident” – a supposed torpedo attack on a US destroyer by North Vietnamese ships. We now know the event never happened, but the lie won Johnson almost unlimited power to escalate the war in Vietnam, with tragic consequences for millions of people. It also set the precedent for fighting undeclared wars that remains a national disaster 50 years later.

*****

I remember a hatchet incident when I was a kid in upstate New York. A boy who lived nearby chopped down a neighbor’s dogwood sapling with a hatchet. This was an especially serious act of vandalism, since dogwood trees were protected by law.

Not the brightest kid on the block, he did so while the lady of the house was home; she heard the chopping, looked out the window, and recognized him. When confronted, however, the boy’s mother said, “It couldn’t have been my son. He told me he didn’t do it, and he doesn’t lie.”

I’ve often wondered if that kid is in politics now. He’d be a natural…

Presidents acting presidential

George Washington, 1797. Public Domain

Our Public Broadcasting System is re-running a series on recent American presidents, first aired in 2013. I missed it then, but caught the second episode of “Kennedy” last night (you can watch the entire program here).

The show was excellent. It outlined several glaring failures of the Kennedy administration: the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion; JFK’s failure to back the emerging civil rights movement; starting us down the slippery slope in Vietnam through mistaking a nationalist revolution for a global communist conspiracy.

Successes included staring down Khrushchev in the high-stakes Cuban missile crisis, and motivating the nation to put a man on the moon, which led directly to the high tech boom, and the laptop or smartphone on which you are reading this post.

Successes and failures aside, the most striking thing I noticed in watching “Kennedy” was that he looked and acted presidential in a way that current presidents do not! Somewhere along the way, the stature and dignity of the office has been diminished.

It’s not that the presidents of my youth were exemplary human beings: Kennedy and Johnson were notorious philanderers, and Nixon was an angry alcoholic, who sometimes gave orders to “bomb the shit” out of countries that annoyed him (see Drinking in America). It’s silly to imagine that those who aspire to the office have changed that much in 50 years. It’s rather that the regard we hold for office has diminished.

True, some people exude charisma, or in Johnson’s case, power. It’s also true that an aura often aura celebrities who die young – Kennedy, Marylin, Elvis, Princess Di, and Prince.

I’m tempted to quote what mythologists like Joseph Campbell and Robert Bly have said about the deflation of the archetypes of king and queen, but I think the answer is far simpler, staring us in the face, in our voracious need to pull presidents down to our level, and their willingness to cooperate.

At the start of the primary season, this year’s crop of contenders gathered in mass for the Iowa State Fair, and one reporter detailed which candidates were truly “just folks,” as opposed to wannabe’s, based on whether or not they knew how to eat ribs.

The cover story on the August 1 issue of Time was, “In Search of Hillary?” What exactly are we searching for? “Likes poetry, puppies and moonlight walks on the beach?”

I remember Cokie Roberts describing a meeting where Lyndon Johnson got angry and chewed someone out. “It took five years off my life,” she said, while noting that recent presidents, wielding the same power, do not command anywhere near that respect. It’s hard to imagine LBJ on Saturday Night Live or with Stephen Colbert, and during this election year especially, I’m not sure that trade of respect for laughter and buddy vibes has been a good deal for anyone.

Whether the loss of respect moves top-down, or bottom-up, or both, when presidential debates begin to look like the Jerry Springer show, and the rest of us behave accordingly, we’re in a world of trouble!

War reporter, Sebastian Junger, author of, Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging, outlined one consequence for us in a PBS interview.

A war reporter, Junger was with troops during “hellish deployments,” but noted that some of the soldiers did not want to go home. Junger says that for most of our history, we humans have lived and thrived most in tribes or clans and, “The real an ancient meaning of tribe is the community that you live in that you share resources with that you would risk your life to defend.”

Only at war did many of the young men that Junger met experience this kind of connection. The lack of it, in our culture, is deadly in his opinion. Looking at our current election season, Junger says we look like opposing tribes, that hold each other in contempt.

“No soldier in a trench in a platoon in combat would have contempt for their trench mate. They might not like them. They disagree with them, but you don’t have contempt for someone that your life depends on. And that’s what we’re falling into in the political dialogue in this country. And in my opinion, that is more dangerous to this country than ISIS is, I mean literally like more of a threat to our nation.”

“I wish I had a tribe,” Junger says, “But we don’t. We just don’t. That’s the problem. That’s why our depression rate, our suicide rate, all that stuff is through the roof. That’s the tragedy of modern society.”

I remember watching Kennedy on TV as a kid. I remember walking to grade school in 1962, past a neighbor who was digging a bomb shelter. I remember “duck and cover” hydrogen bomb drills, which we all knew were ludicrous even then. But through all the fear, what I really remember, was growing up in a neighborhood, in “one nation” as we said during the pledge of allegiance.

I don’t know anyone who lives in a neighborhood or one nation anymore. Perhaps that realization is what makes this election so sad – an election like this couldn’t happen if values like “community,” and “nation,” to say nothing of “tribe,” weren’t so completely fractured.

I have some notions of what happened, but that is for another post. And as they say, we cannot even begin to imagine solutions for a problem until we admit that it exists and what it costs.

Changes

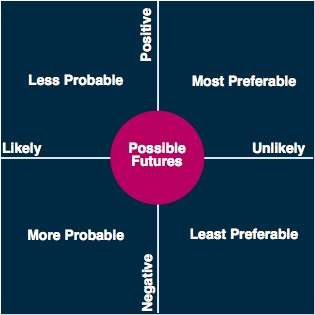

2×2 Matrix: possible futures, by Gaurau Mishra. CC-BY-2.0

Almost four years ago, I posted Change is the Only Constant, a discussion of the December, 2012 report of the National Intelligence Council, a consortium of the 16 major U.S. intelligence agencies. Since 1997, they have issued comprehensive reports on future trends after each presidential election and posted the reports online. We can expect the next installment this winter.

The 2012 edition, which predicts alternate futures for the year 2030, outlines some things that are certain, like aging populations in the developed world; some which are possible, and some “black swans” – potential surprises for good or ill. Here are two key predictions.

- The rate of change in all areas of life will continue to accelerate and will be faster than anything anyone living has seen.

- World population will grow from 7.1 billion (in 2012) to 8.3 billion in 2030. Demand for food will increase 35% and for water by 40%.

Keep this in mind as we look at a some current events. I should preface these comments by saying I’ve long had a rule of thumb: never trust a politician who says, “I have a plan to create jobs.” Both presidential candidates have said those exact words this year.

The fantasy is that by pulling the right levers – cutting or raising taxes, threatening or cajoling China, building a wall at our southern border, and so on, we can restore whatever American golden age our imagination conjures. Maybe the 50’s, when we were the only industrial nation not ravaged by WWII. Maybe the 90’s dot com boom, when even your Starbucks barista had stock tips to share.

We all know that’s not going to happen. The truth is even harder to face than any elected or would-be elected American official has yet been willing to share.

On May 16, the BBC reported that China’s Foxconn, the largest electronics manufacturer in the world, where Apple and Samsung smart phones are made, replaced 60,000 workers with robots. Chinese manufacturers are investing heavily in robotics. So much for bringing jobs back from China.

For an article in the August 1 issue of Time, (“What to do about jobs that are never coming back”), Rana Foroohar spoke to Andy Stern, a former head of the Service Employees International Union: “Stern tells a persuasive story about a rapidly emerging economic order in which automation and ever smarter artificial intelligence will make even cheap foreign labor obsolete and give rise to a society that will be highly productive–except at creating new jobs. Today’s persistently stagnant wages and rageful political populism are early signs of the trouble this could generate.”

In a Common Dreams article published last week, You Can’t Handle the Truth, Richard Heinberg, steps back for a much longer view of our situation and says:

“We have overshot human population levels that are supportable long-term. Yet we have come to rely on continual expansion of population and consumption in order to generate economic growth—which we see as the solution to all problems. Our medicine is our poison.

“And most recently, as a way of keeping the party roaring, we have run up history’s biggest debt bubble—and we doubled down on it in response to the 2008 global financial crisis.

“All past civilizations have gone through similar patterns of over-growth and decline. But ours is the first global, fossil-fueled civilization, and its collapse will therefore correspondingly be more devastating (the bigger the boom, the bigger the bust).

“All of this constitutes a fairly simple and obvious truth. But evidently our leaders believe that most people simply can’t handle this truth. Either that or our leaders are, themselves, clueless. (I’m not sure which is worse.)”

“…any intention to “Make America Great Again”—if that means restoring a global empire that always gets its way, and whose economy is always growing, offering glittery gadgets for all—is utterly futile, but at least it acknowledges what so many sense in their gut: America isn’t what it used to be, and things are unraveling fast. Troublingly, when empires rot the result is sometimes a huge increase in violence—war and revolution.” (emphasis added)

The last major decline of empires, he notes, resulted in World War I. The US and the rest of the world are, in Heinberg’s words, “sleepwalking into history’s greatest shitstorm.”

“…Regardless how we address the challenges of climate change, resource depletion, overpopulation, debt deflation, species extinctions, ocean death, and on and on, we’re in for one hell of a century. It’s simply too late for a soft landing.

“I’d certainly prefer that we head into the grinder holding hands and singing “kumbaya” rather than with knives at each other’s throats. But better still would be avoiding the worst of the worst. Doing so would require our leaders to publicly acknowledge that a prolonged shrinkage of the economy is a done deal. From that initial recognition might follow a train of possible goals and strategies, including planned population decline, economic localization, the formation of cooperatives to replace corporations, and the abandonment of consumerism. Global efforts at resource conservation and climate mitigation could avert pointless wars.

“But none of that was discussed at the conventions. No, America won’t be “Great” again, in the way Republicans are being encouraged to envision greatness. And no, we can’t have a future in which everyone is guaranteed a life that, in material respects, echoes TV situation comedies of the 1960s, regardless of race, religion, or sexual orientation…”

Heinberg’s conclusions aren’t easy to digest, and are tempting to deny. Keeping attention on even a few of the significant points in the articles referenced here leads to disturbing conclusions.

If 16 US Intelligence agencies are anywhere near correct in their numbers, in 14 years, 8.3 billion people will be competing for 40% less water and 35% less food (in this case, living up to their name, the intelligence agencies don’t waste anyone’s time denying the effects of climate change).

Can we imagine “global efforts at resource conservation” in which nations co-operate, and at least try to send relief where it’s needed? Like after tsunamis or the earthquake in Nepal? Or are we headed toward a survivalist wet dream? Futures aren’t set in stone, said the NIA. It all depends on how we behave (sinking feeling in the gut…).

I can see it both ways. Speaking of our current election, someone recently said to me, “I haven’t felt this bad about things since 9/11. Maybe it’s even worse.” Maybe so. In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, we were a nation and a world largely united in awareness of our fragile humanity and revulsion at senseless suffering.

It strikes me that communities often pull together in the face of disaster when our leaders and governments won’t. That is Heinberg’s conclusion as well. Given our lack of competent leadership at the top, how can we build “local community resilience?”

I wish I knew. But since Iceland has more sense than to open it’s doors to American refugees, I’ll have time to think it over! Meanwhile this quote from the Dalai Lama comes to mind:

“We can live without rituals. And we can live without religion. But we cannot live without kindness to each other.”

Changes are certain but futures aren’t set in stone…