Monty Python fans will recognize my title as a reference to Monty Python and the Holy Grail, a hilarious movie which is available on Netflix. Hero tales sometimes include riddles that must be solved or questions that must be answered in order to proceed. In Monty Python’s take on the Arthurian legend, the questions are: “What is your name? What is your quest? What is the airspeed velocity of an unladen swallow?”

On a more serious note…

The idea I want to discuss is that each soul comes into this world with with a purpose which is forgotten at birth and must be remembered for that life to be successful. This is an ancient notion that has appeared in written and oral form for millennia. We find the theme, with variations, in such places as “The Myth of Er” in Plato’s Republic, in The Silver Chair, one of C.S. Lewis’s Narnia Tales, and in James Hillman’s The Soul’s Code, the only one of his many books that became a bestseller.

The idea of such personal destinies came to mind recently as I watched a video by Michael Meade, a storyteller, mythologist, and former colleague of Hillman. He retold an African tale about souls in the Otherworld watching events on earth. When they are drawn to a particular place, situation, or family, they travel with a personal spirit guide to the place of birth. The guide is born with them, as an inner guardian, who will help that soul remember why it chose to be born, as it always forgets when it enters a womb.

In The Soul’s Code, Hillman proposes an “acorn theory” of human development, which he explains is more like a myth than a psychological axiom. As an acorn contains the pattern for the oak tree it will become if circumstances permit, so a child comes into this world with a destiny or “sense of fate.”

It’s important to note that in the first chapter of The Soul’s Code, Hillman explicitly says the book is not addressing questions of “the meaning of life…or a philosophy of religious faith…But it does speak to the feelings that there is a reason my unique person is here and that there are things I must attend to beyond the daily round.”

In an interview first published in 1998 and republished after his death in 2011, Hillman said of his acorn theory, “The same myth can be found in the kabbalah. The Mormons have it. The West Africans have it. The Hindus and the Buddhists have it in different ways — they tie it more to reincarnation and karma, but you still come into the world with a particular destiny. Native Americans have it very strongly. So all these cultures all over the world have this basic understanding of human existence. Only American psychology doesn’t have it.”

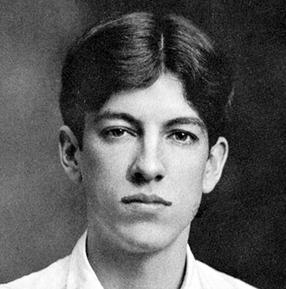

Hillman gives several examples of the difference between his “acorn theory” and the psychological theory of “compensation.” He mentions Manolete (1917-1947), a famous Spanish bullfighter who, as a child, was frail, shy, and “clung so tightly to his mothers apron strings” that even his sisters teased him. Traditional psychological theory would posit that he chose a macho profession to compensate for being a mama’s boy. Hillman turns that argument around. What if a dim awareness of his destiny was present during Manolete’s childhood (his acorn years)? No little boy could handle the intimation of facing charging, thousand pound bulls, so of course he stayed close to his mother!

Hillman never pretends to have a complete set of answers, especially to troubling questions like the origin of “bad seeds,” like Hitler, Manson, or serial killers. Hillman is also cautious of any formulation that would single out kids who are “troublemakers,” noting that Truman Capote was viewed as an “impossible child.”

Meade and Hillman are both concerned with how “ordinary” people find their inner calling, those of us who don’t begin to play the piano or chess at the age of four. Hillman said the “first step is to realize that each of us has such a thing [as a calling]. He then suggests we review our lives, looking especially at “coincidences” or “some of the accidents and curiosities and oddities and troubles and sicknesses and begin to see more in those things than we saw before. It raises questions, so that when peculiar little accidents happen, you ask whether there is something else at work in your life.”

One lifelong thread for me began in childhood, though I would only begin to understand its import years later.

I spent my first nine years in a semi-rural area, with trees to climb, woods to explore, and apples to snitch from the orchard of a farmer who lived over the hill. When my family moved to a quarter acre lot in a suburban California, it often felt claustrophobic. One late afternoon, after everyone had gone home, some impulse led me back to the schoolyard. I lay on my back in the grass of a baseball field and gazed into the clear sky. I don’t know how long I was there, but I didn’t want to get up. When I did, I experienced a refreshing sense of spaciousness and peace.

Several times over the years, at critical moments, I found that same peace and renewal in gazing into the sky, but it was only during the last decade that I learned from a Tibetan lama that sky gazing is a classic meditation practice, often used to teach students “the nature of mind” (clear, like the sky, and unaffected by passing “mental events,” just as the sky is not affected by clouds, rain, or smoke). Such practices became central during the second half of my life.

For both Hillman and Meade, the royal road to understanding and finding our deeper purpose is imagination, and with it, the willingness to listen to the “small” thoughts or impulses we often ignore. Like Joseph Campbell and the first generation Jungians before them, they both look to traditional stories, legends, and myths as means to unlock clues that are hidden within.

Finding our authentic selves, for our own good and the good of a world in transition is a key theme on Michael Meade’s website, Mosaic Voices, where he regularly presents writings, online workshops and podcasts that discuss this and related topics. (He’s presenting a free talk tomorrow, July 13, with a video available afterward – I have no personal stake in this, other than interest).

The consequences of ignoring inner promptings to discover our own authenticity can be devastating. In 1998 Hillman said:

“I think our entire civilization exemplifies that danger. People are itchy and lost and bored and quick to jump at any fix…They have been deprived of the sense that there is something else in life, some purpose that has come with them into the world.”

If this observation, made 25 years ago was relevant then, how much more it is now!!