In literary gatherings, I usually introduce myself as part of the fantasy camp, but I’ve probably read and enjoyed just as many mysteries over the years. In my previous post, I gave a lukewarm review to James Patterson’s latest Alex Cross thriller. I think the real reason is that I’ve never bonded to Alex Cross the way I have to other favorite detectives.

Character is key to detective novels just as it is to other types of fiction, and this is separate from an issue that has surfaced over the last decade, the distinction between plot driven and character driven stories.

In character driven tales, some attribute of the protagonist begins and sustains the action, the way Katniss Everdeen’s sacrifice for her sister gets things moving in The Hunger Games. Mysteries are almost always plot driven – the story begins when the first body is found.

These days, agents and editors say they’re looking for character driven tales. Dan Brown wasn’t listening when he wrote The DaVinci Code, now one of the five best selling books of all time, a distinction shared with The Bible and Harry Potter. Like much advice for writers, I think it misses the point. Regardless of what moves the action, we love novels with characters we love, in worlds we’d love to visit. Have you ever imagined yourself in Baker Street when Holmes jumps up and cries, “The game is afoot?”

If so, read on! I’ve listed a few of my favorite detectives, not necessarily in order, for that, like everything else, is subject to change.

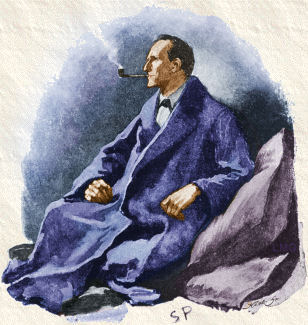

Sherlock Holmes: This is obvious. How many popular books of today will still be read and loved 100 years from now, spawning a lively stream of new presentations in all the popular media of the future? I seldom reread mysteries – often there is no point when you know the criminal’s identity, but I still dive into Holmes for recreation. Has there ever been a more dastardly villain than Dr. Grimesby Roylott in “The Adventure of the Speckled Band?” And for chills up the spine, one sentence has never been beaten: “Mr. Holmes, they were the footprints of a gigantic hound!”

I enjoy all the presentations of Holmes in film, but my favorite movie Holmes is still Jeremy Brett for his perfect blend of genius and madness, without the slightest trace of modesty:

Cadfael: The Brother Cadfael mysteries were the creation of Edith Pargeter, under the pseudonym, Ellis Peters. In early 12th century England, during a period of contention for the crown known as The Anarchy, Cadfael, a middle aged and disillusioned veteran of the crusades, becomes a Benedictine monk. With keen powers of observation, a scientific turn of mind, and an in depth knowledge of herbalism, he solves the many murders that just happen to happen whenever he is near.

I enjoy the film versions more than the books, thanks to renowned Shakespearean actor, Derek Jacobi, who plays Cadfael.

Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple: Most writers are lucky if they can create a single unforgettable character. Agatha Christie gave us two. Sometime in the early 90’s, I went on an Agatha Christie binge, and over the next few years, read all the stories of both characters I could find, some 80 novels in all. Poirot and Miss Marple turn up often in films and on TV. I’ve enjoyed several versions of Murder on the Orient Express and Death on the Nile.

The bad news is that Miss Marple stories are usually classed as “cozy mysteries,” a sub-genre with a distinctly unmanly name. The good news is that I’m too old to care. There is no definitive movie Miss Marple, but British actor, David Suchet takes the honors for his portrayals of Hercule Poirot:

Wallender: To re-establish my manly credentials, I add Kurt Wallender to the list. Wallender is sort of a Swedish, existentialist, high plains drifter, and the most angst-ridden detective in the history of the world. The creation of Swedish novelist, Henning Mankell, Wallendar was adapted for British TV, beginning in 2008. Episodes are show up here on PBS.

The series stars Kenneth Branagh, another great Shakespearean actor. Branagh says Wallender is “an existentialist who is questioning what life is about and why he does what he does every day, and for whom acts of violence never become normal. There is a level of empathy with the victims of crime that is almost impossible to contain, and one of the prices he pays for that sort of empathy is a personal life that is a kind of wasteland.”

Don’t watch this guy when you’re feeling blue!

Jim Chee and Joe Leaphorn: These officers in the Navajo Tribal Police star in 18 mysteries Tony Hillerman wrote between 1970 and 2006. The grandeur of the American southwest and Navajo tribal beliefs are the background against which these unique detective stories unfold. Chee, the younger officer, struggles to hold on to tribal traditions in 20th century America. Leaphorn is more world weary and cynical, but he knows that where there is talk of witches and taboos, trouble erupts.

Hillerman, who died in 2008 loved the four corners and wrote about it so vividly that it’s really another character in the stories. His books won many awards, but he always said what pleased him most was being named a Special Friend of the Navajo Nation in 1987. Adam Beach and Wes Studi starred in three movie versions of Hillerman’s novels, including Skinwalkers, (the Navajo name for malevolent sorcerers), that is regarded as Hillerman’s breakout novel.

Amelia Peabody: Elizabeth Peters’ 19 book series centers on the adventures and detective skills of independently wealthy and independently minded Egyptologist, Amelia Peabody and her family, which at first includes her husband Radcliff Emerson (who hates his first name and refuses to use it), and their son Ramses, who was born as stubborn as his parents. Later Amelia and Emerson take in two wards, David, the son of a Muslim and a Christian whom they rescue from semi-slavery, and Nefret, a red headed former priestess of Isis who will eventually marry Ramses.

Set in the years between 1884 and 1923, there are rascals, rogues, adventurers, tomb robbers, mummy’s curses, and Sethos, aka, The Master Criminal. Historical Egyptologists and archeological events are woven into the series which ends with the 1922 discovery of the tomb of King Tut. The author has said that Amelia herself is based in part on Amelia Edwards, a Victorian novelist and Egyptologist, whose 1873 travel book, A Thousand Miles up the Nile was a best seller.

The middle east has changed since Peters began writing her novels, but they remain among my favorite beach reads of all time. For anyone who enjoys a good mummy movie or has ever fantasized lost tombs, pith helmets, and midnight at the oasis, these are great adventure stories, ever complicated by the corpses that turn up wherever Amelia goes.

I’ve only listed detective series here because I cannot remember every good singular mystery novel I’ve read. Please add any favorites of yours to the list. There’s always room for more, since the game is always afoot somewhere!