Gunnar looks back at his home, 1898 illustration. Public domain.

In order to follow this discussion, it will help if you’ve read two earlier posts:

- Njal’s Saga, an Introduction: http://wp.me/pYql4-2sS

- Njal’s Saga, part 2: http://wp.me/pYql4-2tb

Scholars suggest that the author wove together two separate stories, an oral “Gunnar’s Saga,” and a related but distinct, “Njal’s Saga.” Both men die during attacks on their homes. Historically 18 years passed between the events; Gunnar died in 992 and Njal around 1010. In the last third of the saga, Njal’s son-in-law, Kari, mounts a campaign of revenge against the killers which threatens the stability of the nation. A pitched battle breaks out at the Althing, the National Assembly, which was sacred ground where fighting was forbidden. When reconciliation finally comes, it signifies the dawn of new vision of life and its purpose.

Once the saga gets going, certain scenes come alive like movies – I know there’s a screenplay here…

***

Soon after Gunnar and Hallgerd were married, they attended a feast with Njal and his wife, Bergthora. In no time, the two women were at each other’s throat. The insults grew so extreme that Gunnar dragged Hallgerd out of the hall. Soon after that, she had one of Bergthora’s slaves killed. Bergthora paid her back in kind, initiating a feud that escalated and took the life of free retainers and then kinsmen on both sides.

The killings took place while the husbands were at the Althing which convened for two weeks every summer. Aside from social activities, this was the time for legal action on matters the lower courts couldn’t settle. It was also where “compensation” for killings was determined.

If you killed a man, even in self defense, you confessed it in front of witnesses. A hidden killing was treated as murder and could result in exile for life. A killing confessed was manslaughter and terms of compensation could be set: a slave was worth seven ounces of silver, a freeman fifteen, and a kinsman as much as 200. It may seem cold, but the system was designed to break the cycles of revenge that the old ethic of “honor” and blood retribution entailed.

Gunnar and Njal tried to keep up with the legalities of the killings-for-hire their wives initiated, but it became harder as stakes were raised. Each killing drew more people, bound by family and friendship, into the feud. Into this deadly mix came Mord Valgardsson, son of Unn, who despised Gunnar and Njal.

If Hallgerd spawned chaos and harm, she did so in a half-unconscious manner. She was reactive, without clear designs or premeditation. Mord, by contrast, was cunning, able to weave elaborate snares for his enemies. Our tour leader, Robert Willhelm, pointed out the similarity of Mord’s name to Mordred, King Arthur’s son and nemesis.

During a famine, Hallgerd sent a servant to steal food from a man who refused to sell any to her husband. When Gunnar, with his concept of honor, discovered the theft, he slaped his wife, who had already buried two husbands who hit her. Hallgerd warned Gunnar that she would never forget the blow.

Njal prophesied that if Gunnar killed two members of the same family and broke the legal settlement for the killings, he would die soon after. Through trickery, Mord ensured that Gunnar killed the son of a man he’d already slain. In addition to a financial settlement for the killing, the Althing court sentenced Gunnar to three years in exile.

In one of the most poignant scenes, as Gunnar and his brother rode to the harbor, Gunnar’s horse slipped while fording a river. Springing off the horse, Gunnar looked back at his farm and said, “Lovely is the hillside – never has it seemed so lovely to me as now, with its pale fields and mown meadows, and I will ride back home and not leave.”

That autumn, Mord sent word that Gunnar was home alone and 40 of his enemies mounted an attack. Firing arrows from the second floor, Gunnar killed two assailants and wounded eight. Then a man named Thorbrand got close enough to cut Gunnar’s bowstring.

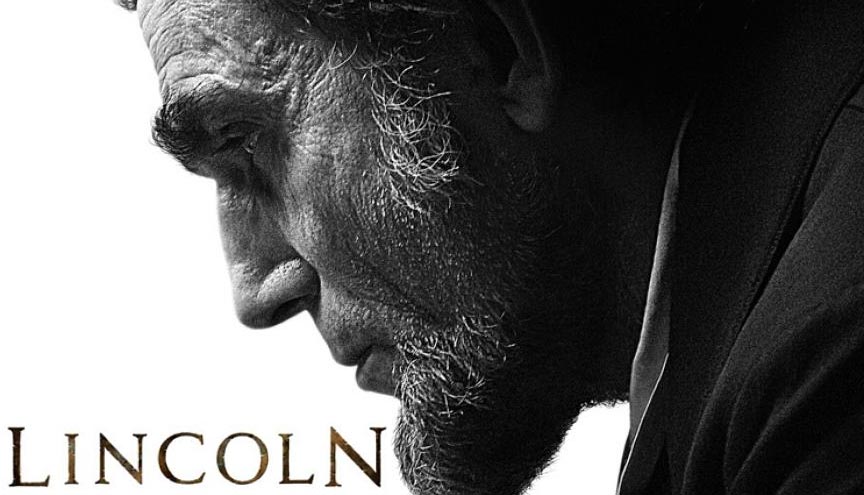

Gunnar defending his home, 1898. Public domain.

Gunnar turned to his wife and asked for two strands of her waist length hair for a new bowstring. Hallgerd said, “Does anything depend on it?”

“My life depends on it,” Gunnar said, “for they’ll never be able to get me as long as I can use my bow.”

“Then I’ll recall,” she said, “the slap you gave me, and I don’t care whether you hold out for a long or short time.”

Gunnar wounded eight more attackers before he finally fell, exhausted and wounded in fifteen places. One of the attackers said, “His defense will be remembered as long as this land is lived in.”

Gunnar’s mother was ready to kill Hallgerd who fled the house. Gunnar’s friends raised a burial mound, and one night, as two of Njal’s sons passed by, they saw the mound open. Four lights shone and cast no shadows. The brothers heard Gunnar’s spirt sounding content as it spoke skaldic verse.

***

Gunnar embodied the old warrior ideal of life and death with honor that won you a place in Valhalla. The dark side of this ethos was an unending string of killings that threatened the nation itself. Things were about to change. Shortly after Gunnar’s death, a Christian missionary named Thangbrand arrived in Iceland. He wasn’t the sort of evangelist you want on your doorstep, since he carried a crucifix in one hand and a sword in the other and didn’t much care which he used.

One autumn morning, as Thangbrand celebrated mass, a man named Hall of Sida approached. “In whose memory are you celebrating this day?” he asked.

“The angel Michael’s,” Thangbrand said.

“What features does this angel have?” Hall asked.

“Many,” said Thanbrand. “He weighs everything that you do, both good and evil, and he is so merciful that he gives more weight to what is well done.”

Hall said, “I would like to have him for my friend.”

With his openness to new ideas and the simple way he voices his spiritual longing, Hall becomes the first convert. In 999 or 1000, the Althing declared Christianity to be the new religion. Mord continued to work behind the scenes fomenting trouble for Njal and his sons, and around the year 1010, 100 armed men attacked Njal’s home and burned it, with him and most of his family inside. Only Kari of Orkney, Njal’s son in law, escaped. He raised a force to attack the burners, and at the next Althing, when the retribution process broke down, a pitched battle erupted at Thingvellir, the spiritual heart of the nation.

Battle at Thingvellir. Public domain.

During a lull in the fighting, members of the assembly intervened to arrange a truce. Hall of Sida stood between the combatants and said, “All men know what sorrow the death of my son Ljot has brought me. Many will expect payment for his life will be higher than for the others who have died here. But for the sake of a settlement I’m willing to let my son like without compensation, and what’s more, offer both pledges and peace to my adversaries.”

Things have changed. A few decades earlier, such a statement would have cost Hall his honor, but the saga says that when he sat down, “much good was spoken about his words, and everybody praised his goodwill.”

The combatants submitted to judgement. Cash payments were levied as well as three years exile from Iceland for the combatants. During the exile, they slew each other in Orkney and along the coast of Ireland, but finally, when the leaders returned to Iceland, they pledged friendship to each other. The old ways had cost too much in blood and suffering. The survivors had no stomach for anymore fighting. The saga ends with a sense that a new wind was blowing through the land.

Next: reflections on the story.