If you haven’t already done so, I suggest you read the preceding post, Notes on Trickster stories, which provides a background and context for this article. Both posts were inspired by “The North Wind’s Gift,” a tale from Italo Calvino’s Italian Folktales, 1956. The story came to my attention in Allan Chinen’s discussion of tricksters and appealed because of its relative simplicity and relevance to our own times.

Here’s a synopsis of the story:

Once there was a farmer named Geppone who toiled in his fields every day of the year but could barely feed his wife and three children. The North Wind blew at harvest time and ruined his crops. Finally Geppone had enough and set out to find the North Wind and demand justice. He reached the North Wind’s castle. “Every year you ruin my crops,” he said. “Because of you, my family is starving to death.”

“What can I do?” the North Wind asked.

“I leave that up to you,” Geppone replied.

The North Wind’s heart went out to the little farmer. He brought out a box. “This is a magical box which will give you food when you open it, but tell no one else about the magic or you’ll lose it.”

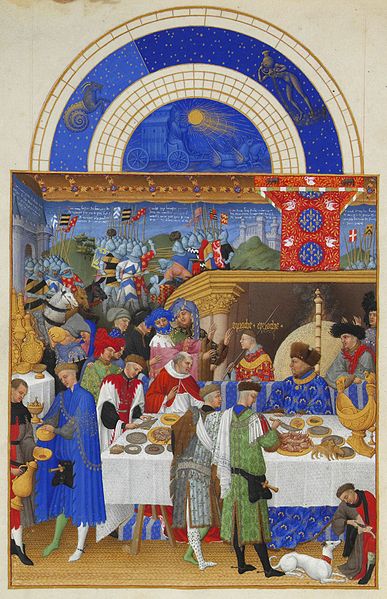

Geppone thanked the Wind and set out for home. On the way, he opened the box. Instantly a table appeared, piled with food. When he got home, Geppone opened the box again and treated his family to a feast. He told his wife not to tell anyone, and especially to say nothing to the priest, who was their landlord and a greedy man.

The next day, the priest spoke to Geppone’s wife and wrung the story out of her. He summoned Geppone and demanded the box on pain of eviction, offering seeds in return, which proved to be worthless. As bad off as he was before, the farmer returned to the North Wind’s castle to ask for another boon.

At first, the North Wind refused, saying, “You ignored my warning. Why should I help you again?” Geppone pleaded, and reminded the Wind that he was still the cause of the family’s ruin.

“Very well,” said the North Wind at last. He gave Geppone a magnificent gold box, but said, “Open this only when you are starving.”

On his way home, Geppone stopped and opened the new box. This time a ruffian with a club jumped out and began to beat the farmer, who struggled to close the lid. When he did, the ruffian vanished. Geppone limped home, sore and bruised. When his wife and children clamored to try the golden box, Geppone left the room. This time two ruffians jumped out and began to beat the family. Geppone slipped back into the room, closed the box, and the assailants vanished.

“This is what you must do,” he said to his wife. “Tell the priest I brought home an even finer box, but say nothing else.”

Geppone’s wife understood and did as her husband instructed. When the priest called the farmer and demanded the golden box, Geppone feigned reluctance, but at last agreed to trade it for the original box. The priest rubbed his hands. The bishop was due to join him for Mass the next day; a feast would be just the thing to win the approval of his superior.

The next day, after Mass, the priest, the bishop, and their retinue gathered for supper. When the priest opened the box, six ruffians jumped out and beat the clerics. Geppone, who was waiting at the window, took his time in closing the box to save them.

No one objected when he carried this second box home. The priest never bothered Geppone again. The farmer was careful to guard the North Wind’s gifts, and his family lived in ease and comfort for the rest of their days.

You can read the story as it appears in Italian Folktales here: The North Wind’s Gift

***

It’s clear at the start of the story that we’re in a post-heroic fairytale world. Geppone is not out to slay a dragon, rescue a princess, or win a kingdom – he just wants to survive.

Allan Chinen speaks of the different life stages that different fairytales address. While the majority center on young people venturing into the world, “middle-tales” like this have older protagonists with different kinds of problems. From a Jungian perspective, Chinen notes that tricksters usually don’t show up in our dreams when we’re 18 and planning to take the world by storm – they visit us when we’re 40, with a mortgage, a couple of kids, and a car that needs an engine overhaul.

Geppone works from dawn until dark but can barely make ends meet. His wife doesn’t listen to him, and the landlord threatens eviction. This setup makes his story seem contemporary – if we’re not in this situation ourselves, one of our neighbors probably is.

We get the feeling Geppone has been down on his luck and taking it on the chin for a while. Something finally awakens within him and spurs him to action. As a result, he meets the North Wind, a wild spirit who will become his guardian and mentor and teach him the wiles of the trickster.

The North Wind is invoked in the Song of Solomon, in Aesop, and in Greek and Norwegian folklore. He shows up in George McDonald’s novel, On the Back of the North Wind, in the stories of Hans Christian Anderson, and in Pokemon. The North Wind is also associated with thunder gods like Zeus and Odin. It’s not surprising that he is a shadowy trickster in Italy, where invaders and winter both arrive from the north.

Almost every successful fairytale character wins the help of a guiding spirit, and the North Wind’s help is just what Geppone needs. It prompts him first to stand up for himself and ask for what he needs and then to learn enough strategy to overcome his oppressive priest and landlord. To Jungians, fairytale allies like helpful animals, fairy godmothers, and nature spirits represent parts of the unconscious mind that are older and wiser than ego, which gets us into trouble in the first place.

What this means in practical terms is a vast subject, beyond the scope of a few blog posts. Jung would suggest to patients who were comfortable in a religious tradition to return to it for guidance. Much of Jung’s work aimed at helping people estranged from existing traditions who still needed to tap inner sources of wisdom.

In the “Power of Myth,” Bill Moyers asked Joseph Campbell where ordinary (i.e., busy) people might look to experience the wisdom of myth. Campbell suggested we take 30 minutes or an hour a day in a quiet place where we can read what inspires us and perhaps keep a journal.

Just like this story, the psyche is home to ruffians and riches, and the old stories are not to be taken literally. James Hillman, a prominent Jungian thinker, always insisted that literalism is the greatest enemy of inner wisdom. So how does trickster wisdom manifest in our world right now? I don’t think we have to look very far.

A world that’s increasingly dysfunctional serves as a magnet for trickster energy, for good as well as for ill. A Facebook friend mentioned that he once loaned out a book on trickster mythology and never got it back. That fits the myths of trickster gods like Hermes who are also patrons of thieves. Hermes may be the supreme image of the trickster. As fluid as the metal which bears his Roman name, Mercury, he was the messenger between gods and humans who also conducted souls to the afterlife. Patron of travelers, herdsmen, poets, orators, athletes, and inventors, his herald’s staff, the caduceus, is the symbol of healing to this day.

I find myself watching for positive manifestations of trickster energy, which usually turn up under the radar of corporate and government organizations which carry a vested interest in the status quo. When you look, quite a few individuals and groups are trying out new solutions. I’ll post at least one example in the near future.

In the meantime I would love to hear where you find trickster energy in yourself and in those around you.

![]()

Some (very reputable) psychologists are absolutely convinced that DNA is destiny. Other (very reputable) psychologists are convinced that your personality is shaped by what happens to you as an infant – or perhaps even in the first few minutes of life. This is what I love about psychology: the theories are all over the map and yet somehow everyone is still credible.

Some (very reputable) psychologists are absolutely convinced that DNA is destiny. Other (very reputable) psychologists are convinced that your personality is shaped by what happens to you as an infant – or perhaps even in the first few minutes of life. This is what I love about psychology: the theories are all over the map and yet somehow everyone is still credible.