Sam Peckinpah was 48 when he directed Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. His health was failing after too many years of drug and alcohol abuse; a documentary I saw showed the crew carrying him from one scene to another on a stretcher. He was also battling the studio for artistic control of the project, a fight that he lost. Critics panned the production release of the movie, though 10 years later, when the director’s cut was available, they praised it as one of his finest.

Peckinpah poured his heart and soul into this tale of a rebel who died too young. It isn’t hard to see the connection. Maximilian Le Cain, a filmmaker living in Ireland, says:

[Peckinpah’s] finest works are permeated with an intensely haunting atmosphere of melancholy, loss, and displacement. His heroes are exiles, men out of step with their dehumanised times, alienated from love or domesticity, yearning for a redemption that they seem able to find only in self-destruction. It is a dark but intensely romantic vision. If for nothing else, Peckinpah admires his heroes for their staunch individualism in the face of a world that is changing for the worse, eroding under the blindly ruthless power of money. http://archive.sensesofcinema.com/contents/01/13/garrett.html

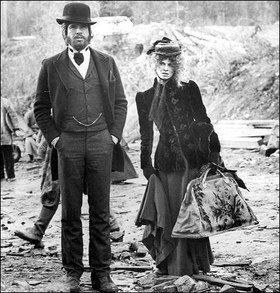

One summer saturday afternoon in 1973, I went to see Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. I walked out of the theater stunned, went home and got my sister, and saw the movie again. In the months and years that followed, I read everything I could about Billy the Kid. I made a series of prints called, “Homage to Billy the Kid” (the one that survives is shown below). Two years later, my wife and I explored Lincoln County, New Mexico, where the key events of William Bonney’s life played out.

Homage to Billy the Kid, color etching by Morgan Mussell, 1973

It isn’t hard to understand why I resonated with Billy the Kid’s story. “Billy, they don’t want you to be so free,” sings Bob Dylan in the title song. I was an art student, stuck that summer in a western New York factory town, longing for the southwestern deserts where the skies and vistas are so open they don’t seem real. Times were hard; the sixties were over; just as in the late 19th century, the price of being “out of step” had gone up.

Some biographies paint William Bonney as an engaging rebel, and others as a psychopathic killer. I doubt that there is any chance of extracting the “real” William Bonney from legend, but one thing appears to be historical fact: Billy the kid would not have been declared an outlaw if he had fought on the winning side of “the Lincoln County War,” a bloody open-range type conflict that culminated in a pitched battle on the streets of Lincoln. There were no angels in that fight; no one deserved a white hat.

Not only is Pothos, the unrequited longing for “something more,” beautifully evoked by Kris Kristofferson’s portrayal of Billy, it permeates the New Mexico landscape and sky, which is like another character in the movie: it mirrors the Kid’s doomed quest to “live free” with an extraordinary beauty that we glimpse but can never grasp and hold.

Perhaps the best known artifact of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid is Bob Dylan’s elegy, “Knocking on Heaven’s Door,” which sets the tone for the whole movie in its most haunting scene:

Knocking on Heaven’s Door in Peckenpah’s “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid”

In an effort to find the Kid, Garrett seeks out another town’s sherif, Colin Baker (Slim Pickens), a man so disillusioned he has to ask his wife where he left his badge. He is building a boat in his yard – a pathetic dingy – so he can “drift out of this damn territory.” Baker, his wife, and Garrett raid the hideout of a former member of Billy’s gang, and Baker is mortally wounded. He stumbles over to die by the little creek he hoped to sail away on, and we see it is too shallow to float anything larger than a paper boat.

Sam Peckinpah grew up outside Fresno and used to cut school to cowboy on a relative’s ranch. According to Maximilian Le Cain (citation above), he did his best to live the myth of the hard living, hard drinking, womanizing, knife-throwing free spirits whose stories he tells. Cain believes that when Peckinpah started Pat Garrett, he understood and set out to reveal the emptiness of this way of life – its inability to satisfy the hunger within. He says:

Pat Garrett presents us with a country full of men without a future…If the Western is fundamentally about a struggle for survival in the face of a hostile wilderness, Pat Garrett is about people just waiting around to die. If the West is a wide-open country, Peckinpah’s sees it as a prison from which almost every decent person is trying to escape.

Quite a few movies came out debunking the myth of the west in the decade after that optimistic western epic, How the West Was Won (1962). Many of these films were politically motivated in an era when, if the body count from Viet Nam was too depressing, you could flip to the ironclad righteousness of the Cartwright boys on Bonanza.

Superficially, Pat Garrett, appears to fit into this group of largely forgotten movies, but it is more. What lifts it above the myth-busting movies, according to Maximilian le Cain, is Peckinpah’s love of the genre:

Unlike the revisionists, [Peckinpah’s] best films were at least partially self-portraits as opposed to ‘issue’ movies. He exposed the emptiness at the heart of the myth from the inside with the same anguish that he might feel in disclosing a fatal disease from which he was suffering. It is this depth of feeling that really sets this film apart from its contemporaries and has ensured its survival in the face of time.