This unusual job description comes from the opening lines of a Grimm’s fairy tale I recently read for the first time. Fairy tale characters never get more than a word or two of description, and most of the time, tags like “clever fox” and “evil stepmother” are so familiar they don’t make us stop and think. The opening of “The Glass Coffin,” was different enough to catch my attention:

“A civil, adroit tailor’s apprentice once went out traveling, and came into a great forest, and as he did not know the way, he lost himself.”

Civil and adroit are good terms for key attributes of successful folklore protagonists. Though the words may sound quaint to us now, the traits they describe are as relevant to our own world as they are to travelers in Faerie.

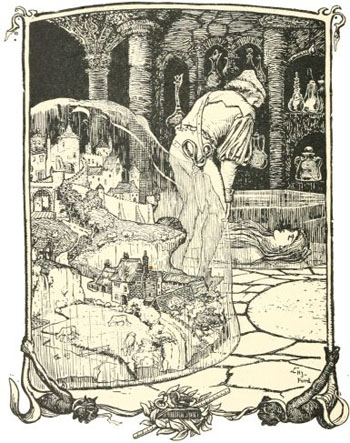

The Glass Coffin

The virtue of civility:

Some of the Grimm Brothers’ stories seem to locate these attributes along gender lines, implying a world of civil females and adroit males. But if we review a number of tales, much of the time we find both characteristic needed by men and women alike.

Girls who are rude or mean may wind up dead or have their eyes pecked out like Cinderella’s step sisters. Toads may jump from their mouths when they try to speak. Feminists point to such story features as efforts to domesticate young women and make them docile. Yet for many youngest sons, success also hinges on civility, often to seemingly insignificant creatures. It’s a dwarf who offers council in The Water of Life. When the worldly-wise older brothers mouth off to the little man, they end up imprisoned in stone. The youngest brother, who is respectful and heeds (most of) the dwarf’s advice, wins his heart’s desire and more.

In many of these stories, motives are greater than simple expediency. The hero of The White Snake shows genuine compassion.

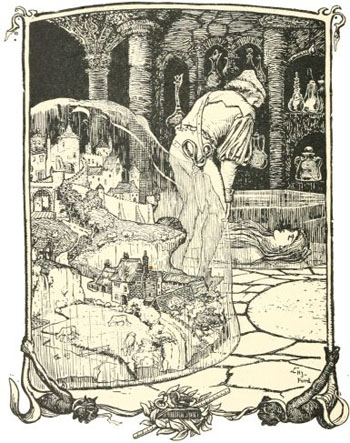

The White Snake by Arthur Rackham

Through a bit of (adroit) trickery, a king’s servant gains the power to understand the speech of animals. He goes traveling and saves three different kinds of “lowly” creatures – fish, ants, and baby ravens. Kind heartedness rather than self-interest drives him, for though the creatures promise to help him, they only do so after he sets them free. There were no strings attached to his generosity.

The story is not just a simple call to spare the lives of all creatures, for the servant kills his horse to feed the ravens. It would take another post to explore this detail, but to the extent that these stories dwell on compassion, their theme is both ancient and timely. The Dalai Lama put it in simple terms: “If you want others to be happy, practice compassion. If you want to be happy, practice compassion.”

The virtue of being adroit:

The dictionary defines adroit as “skillful in a physical or mental way; clever; expert.” In fairy tales, this sometimes means knowing when to kill your horse to feed the ravens. At other times, it means cunning, trickery, and lies. In stories, we often imagine these as men’s attributes, perhaps because traditional full time tricksters, from Hermes to Coyote, are usually male. Yet in Grimm’s stories, young women need to understand and master deceit as often as men. In Bluebeard-type tales, and notably a frightening story called “Fitcher’s Bird,” it’s a matter of life and death.

Part of being adroit is the intuitive sense of when someone or something feels wrong; when civility is not in order. In fairy tales, women often do this better than men. Typically, in three-brother stories, the youngest prince will trust his older brothers, even after the dwarf has warned him not to. Cinderella and girls like her know better than to be fooled by older siblings.

Instinctively knowing when something is off has new relevance in the 21st century. Interviews with 9/11 survivors adds to research suggesting our brains are not very good at processing radical changes or threats. People on the upper floors of the South Tower had just over 16 minutes before the second airplane hit; those who left survived and those who waited did not. On average, people took 1o minutes to choose. In times of radical change, we need that cunning, adroit part of our ourselves to cut through the illusion that things will right themselves and return to “normal.” It can be a matter of life or death.

***

Few things in fairy tales are certain, and the first story in the Grimm’s collection, The Frog King, is an exception that proves the rule proposed by this post. The princess is neither civil nor adroit. She’s a petulant brat, who gets what she wants by hurling the frog against a wall (the kiss only comes in later versions). To our sensibilities, she doesn’t deserve the prince who appears when her act of violence breaks the spell.

There’s an irony in the original “Frog King,” however. When the transformed prince reunites with his faithful servant, Heinrich, he almost seems more delighted than he is with his new bride. At least one illustrator, Walter Crane (1845-1915) implies that the princess won’t have everything to her liking. Who does the prince have eyes for in the closing scene, and how does the princess appear to react? Does this story end with a twist that the Brother’s Grimm shied away from?

The princess, the prince, and Heinrich in Walter Crane’s 1874 illustration.

Experienced explorers warn us that the way through Faerie is perilous. Trails may shift beneath our feet, and hard-and-fast rules don’t apply. As Joseph Campbell observed, everyone must find their own way through the forest.

My latest exploration leads me to wonder if “adroit” is another word for “street smarts,” something we need in our own world as well as in dark imaginal forests and castles frozen in time. And isn’t “civil” an attitude that understands that our own wellbeing, even in the most practical terms, must include the welfare of others?

The old stories may offer no certain answers, but with careful reading, they can always lead us to ask interesting questions.