Looking at Malcolm Forbes’ toys in the previous posts reminded me of one of my favorite American artists, Joseph Cornell (1903-1972), who built windows into our dreams, into other times, and other worlds.

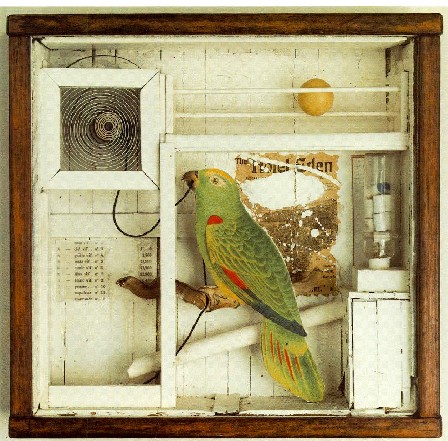

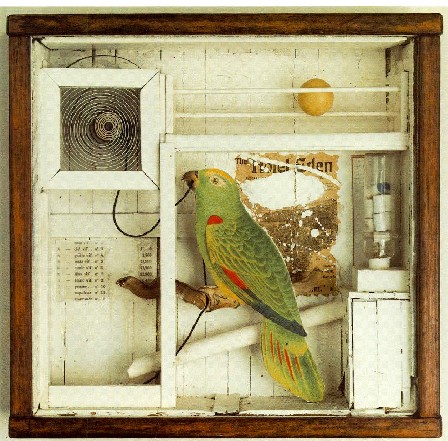

Untitled (Hotel Eden) ca. 1945

Cornell, who was wary of strangers and self-taught as an artist, led a reclusive life, most of it in a wood-frame house in a working class neighborhood in Queens. Though he had galleries and collectors from an early age, I have never seen him listed among the “major” American artists of the 20th century. One of my college art history professors suggested he was “ahead of his time,” in the missed-the-boat sense, noting that in the 60’s, Robert Raushenberg gained art world super-star status with constructions and collages similar to those Cornell had begun in the 30’s.

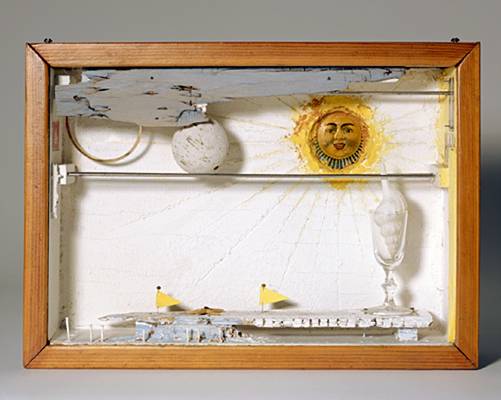

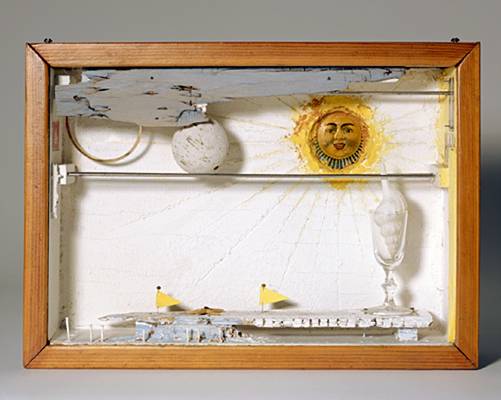

Setting For a Fairytale

I think there was much more to it than that; I find it significant that Cornell, described as “frighteningly well read,” had a special affection for the poetry of Emily Dickinson, another reclusive soul, and Arthur Rimbaud, who firmly rejected the literary and artistic “establishment” of his time.

Cornell said what he wanted in his art was “white magic.” It’s hard to imagine such a subtle ambition surviving the grand gestures and conscious self-promotion of the artists of Warhol’s generation. Cornell’s distance from that mileau seems to have been deliberate.

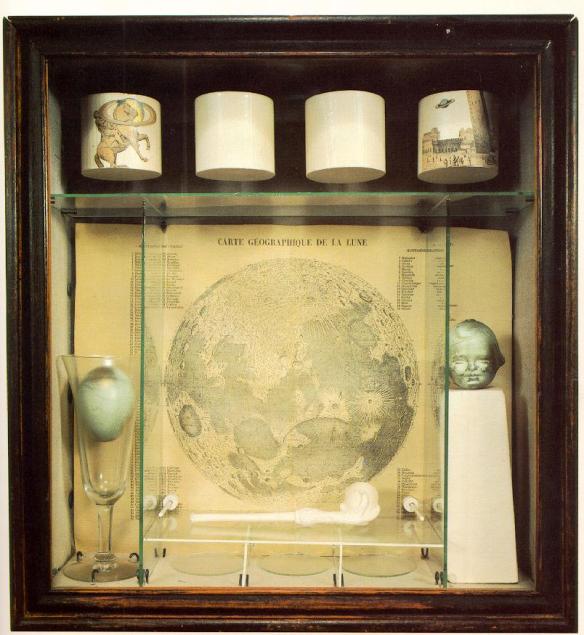

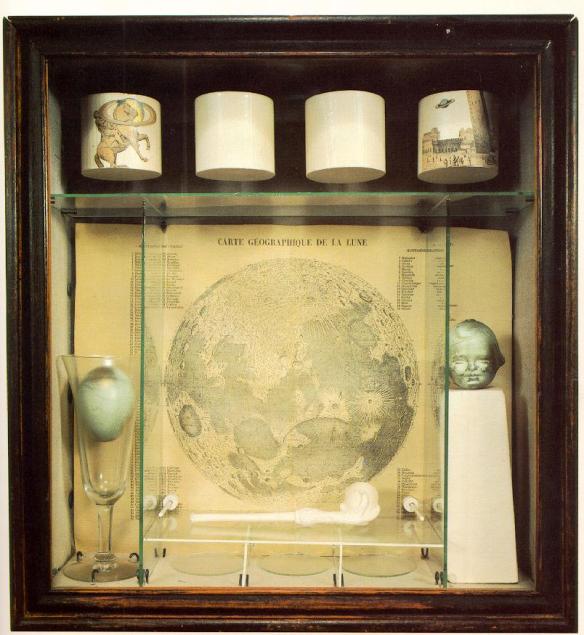

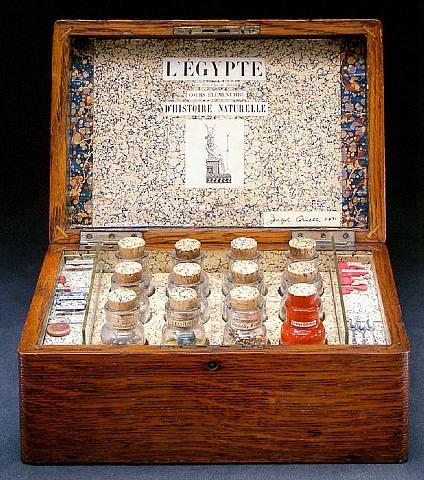

Untitled (Soap Bubble Set) 1936

In a wonderful article on Joseph Cornell in 2003, the centennial of his birth, Adam Gopnik says:

What’s nostalgic in Cornell’s art is not that it’s made of old things…What’s nostalgic is that, behind glass, fixed in place, the new things become old even as we look at them: it is the fate of everything, each box proposes, to become part of a vivid and longed-for past…a bottomless melancholy in the simple desolation of life by time. The false kind of nostalgia promotes the superiority of life past; the true kind captures the sadness of life passing.

http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2003/02/17/030217crat_atlarge?currentPage=1

Gopnik says Cornell’s much-storied isloation was central to his way of working.

He had discovered the joys of solitary wandering. Beginning in the early nineteen-forties, his life was structured by a simple rhythm: from Queens via the subway to Manhattan, where he walked and ate and watched and collected, and then back home to the basement and back yard in Queens, where he built his boxes, talked to his mother, and cared for his brother (who had severe cerebral palsy).

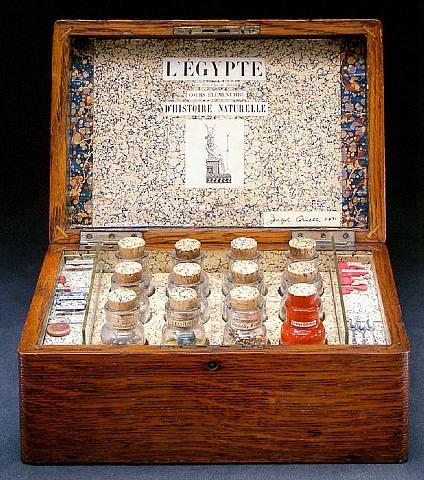

Certain themes recur in the work of Joseph Cornell: birds, ships, the requisite surrealist clocks, and bottles which hint at potions or hidden alchemical mixtures.

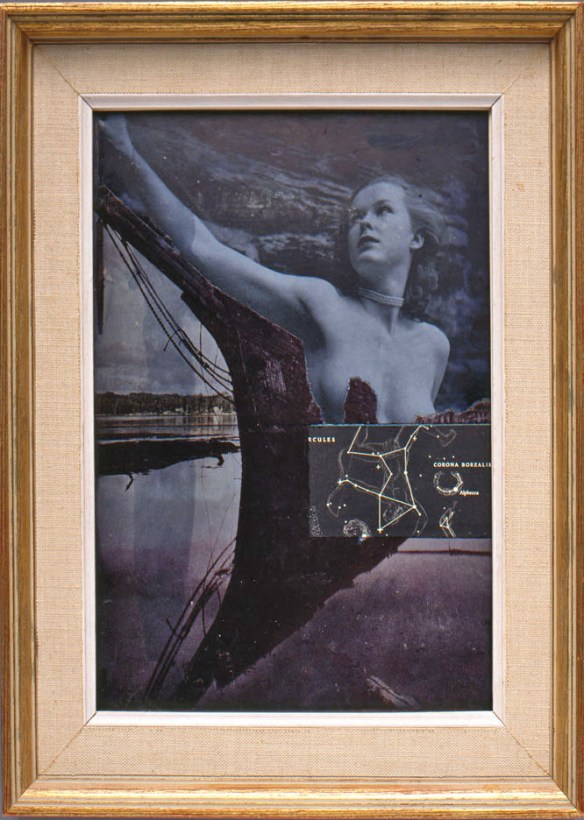

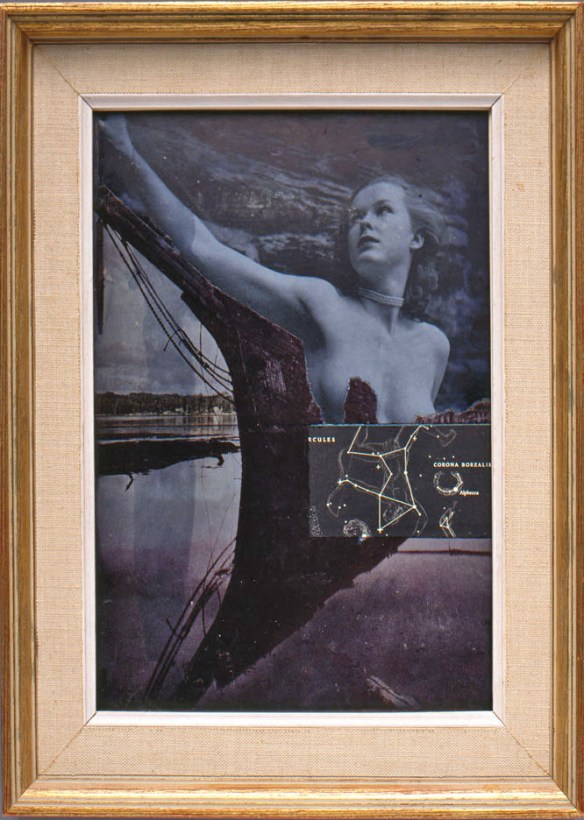

Another recurring theme is idealized images of women.

Ship With Nude

Although he professed devotion to unattainable women like Lauren Bacall and Marylin Monroe, his reserve kept him out of romantic relationships as far as anyone knows. At the same time he was friends with numerous ballerinas, including Tamara Toumanova, a “superstar” in the world of ballet at a time when Cornell had gained some prominence in the world of art. Several of his pieces are homages to Tourmanova.

The final exhibition Cornell worked on during 1972, the last year of his life, was for “children only.” Everything was placed at their eye level, about three feet above the floor. Denise Hare writes: “Joseph Cornell often said children were his most receptive and enthusiastic audience. They were filled with innocence and needed to see.” Brownies and cherry coke were served as refreshments.

Cornell at an exhibition of his work for children at Cooper Union, 1972

In his 2003 article, Adam Gopnik says:

He is an artist of longings, but his longings are for things known and seen and hard to keep. He didn’t long to go to France; he longed to build memorials to the feeling of wanting to go to France while riding the Third Avenue El. He preferred the ticket to the trip, the postcard to the place, the fragment to the whole. Cornell’s boxes look like dreams to us, but the mind that made them was always wide awake.

***

Joseph Cornell showed us again and again that just a little shift in context, an altered point of view on the things of our lives will make them come alive, seem full of meaning, or appear as downright spooky.

The core importance of context in art was demonstrated forcefully in 1917 by Marcel Duchamp’s whose “ready-made” sculpture, Fountain, was named “the most influential piece of modern art” by 500 artists and critics. Duchamp hung a urinal upside down in a gallery, signed it, “R. Mutt,” and to my mind, truly initiated the twentieth century in art. Duchamps and Cornell were in regular contact in New York from 1942 to 1953.

Fountain, by Marcel Duchamp

Cornell never sought to shock as Duchamp did, or ask huge questions, like “what is art after all?” But he regularily explored what happened when the faded postcard or torn photograph was removed from the shoebox or dusty album and given new life in a box on a wall. And there, some of his birds and ballerinas still live mysterious lives and whisper to us messages which we have to become very quiet to hear, for as T.S. Eliot put it, Human kind cannot bear very much reality.

***

Click here for an interesting online Presentation of Cornell’s Work: http://www.pem.org/exhibitions/62-joseph_cornell_navigating_the_imagination