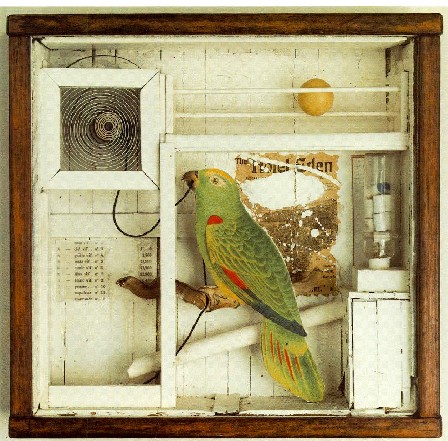

It was a golden afternoon; the smell of the dust they kicked up was rich and satisfying - Illustration for The Wind in the Willows by Arthur Rackham, 1940

Kenneth Grahame was a turn of the century British author who was Secretary of the Bank of England “in his spare time” (according to A.A. Milne). In 1908, Grahame published The Wind in the Willows, his third novel. Unlike his first two books, The Wind in the Willows was not an immediate success, though its early supporters included Theodore Roosevelt, who wrote to the author in 1909, “I have read it and reread it, and have now come to accept the characters as old friends.”

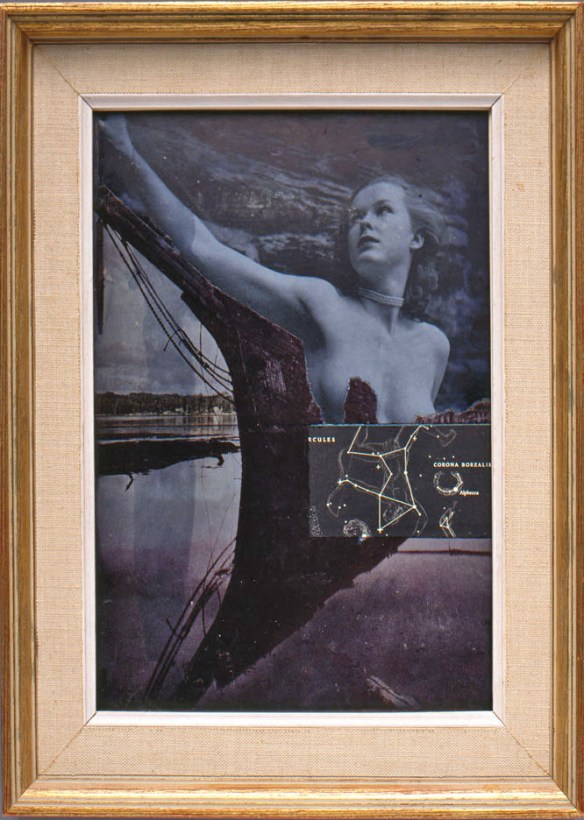

Arthur Rackham was perhaps the best known artist of “the golden age of illustration,” from 1870-1930. His illustrations for The Wind in the Willows were his last work, published posthumously in 1940, a year after Rackham died of cancer.

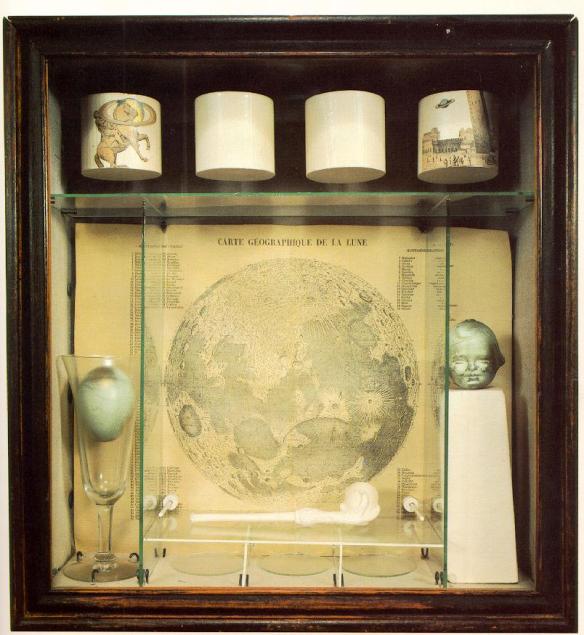

Shove that under your feet, he observed to the mole, as he passed it down into the boat - Arthur Rackham, 1940

I cannot think of a more auspicious partnership in the history of book illustration, though I am biased. I’m writing about The Wind in the Willows because I stopped by a blog that asked, “What is your favorite book?” This has been mine since my mother read it to me when I was four. When she finished, I begged her to start it again. I began school determined to learn to read as soon as I could so I would not have to wait on anyone else’s convenience to row up the river with Rat and Mole.

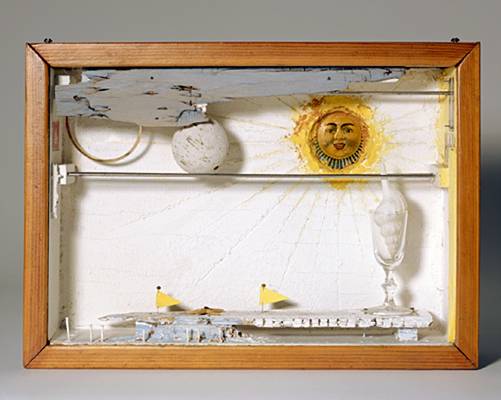

The badger's winter stores, which indeed were visible everywhere, took up half the room - Arthur Rackham, 1940

I called this post an appreciation rather than a book review, because my intent is not to be systematic. Besides, in his introduction, A.A. Milne warns us not to dare anything so foolish:

One does not argue about The Wind in the Willows. The young man gives it to the girl with whom he is in love, and if she does not like it, asks her to return his letters. The older man tries it on his nephew, and alters his will accordingly. The book is a test of character. We can’t criticize it because it is criticizing us.

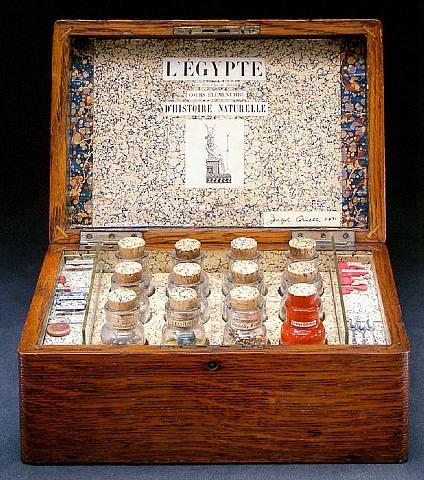

She arranged the shawl with a professional fold, and tied the strings of the rusty bonnet under his chin - Arthur Rackham, 1940

The magic of this volume lies in text as well as the illustrations. This is story of friendship, of terror in the Wild Wood, of the ache of standing outside looking in on Christmas eve. There is slapstick and comedy, and a battle against heavy odds to restore the natural order along the river bank, but the center of the story for me has always been Chapter 7, “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.”

Otter’s son Portly has gone missing, and one mild summer evening, Rat and Mole row the backwaters trying to find him. They catch the strains of a haunting tune:

“It’s gone!” sighed the Rat, sinking back in his seat again. “So beautiful and strange and new! Since it was to end so soon, I almost wish I had never heard it. For it has roused a longing in me that is pain, and nothing seems worth while but just to hear that sound once more and go on listening to it for ever. No! There it is again!”

The animals follow the sound and it leads them to a place where a great Awe falls upon them and they are granted a vision: [Mole] raised his humble head; and then, in that utter clearness of the imminent dawn, while Nature, flushed with fullness of incredible color, seemed to hold her breath for the event, he looked in the very eyes of the Friend and Helper.”

The animals find the baby otter and the vision fades, leaving them in misery as they feel what they have lost, but then, a capricious little breeze, dancing up from the surface of the water, tossed the aspens, shook the dewy roses, and blew lightly and caressingly in their faces, and with its soft touch came instant oblivious. For this is the last best gift that the kindly demigod is careful to bestow on those to whom he has revealed himself in their helping: the gift of forgetfulness. Leset the awful remembrance should remain and grow, and overshadow mirth and pleasure, and the great haunting memory should spoil all the after-lives of little animals.

The minister in the church I attended when I was young once said from the pulpit that “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn,” was the best theology he knew outside the Bible.

Together, Kenneth Grahame and Arthur Rackham preserved and shared a vision of an older, idyllic England of quiet lanes and riverbanks and launched it into a new century that needed such a dream, after one World War and on the eve of a second. Last time I looked for a gift for a friend, a facsimile edition was available (from Modern Library I believe).

There are other nice editions like the one illustrated by Michael Hague and published in 1980, for there are more ways than one into this dream.

Wind in the Willows cover by Michael Hague, 1980

I guess you could say I’ve been dreaming along with the great British storytellers all my life – with Rat and Mole, with Pooh and Piglet; in Middle Earth and Narnia; with King Arthur and his knights; with Welsh wizards and Irish warriors and Tam Lin in Faerie; Harry Potter is simply the latest feast from the cornucopia I first encountered when I was four years old.

If you have not yet discovered the magic of The Wind in the Willows (and I don’t mean Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride @Disney) I suggest you give it a look as soon as can. In my experience (as in Bilbo’s) there is no telling where the road will take you.

The wayfarer saluted with a gesture of courtesy that had something foreign about it - Arthur Rackham, 1940