Njal’s Saga. 13th c. manuscript page. Public domain.

Those who follow this blog have seen messages and photographs from Iceland over the last two weeks. Mary and I spent a week there with Robert Bella Wilhelm and two other storytellers. Several decades ago, Robert and his wife, Kelly, created “Storyfest Journeys” to lead small groups of people on “storytelling travel seminars.” http://www.storyfestjourneys.com

We discovered Storyfest Journeys in 1991 and spent a memorable week in west England and Wales on a themed trip, “The Quest for Arthur’s Britain.” Since then we’ve joined the Wilhelms in Arizona and New Mexico for seminars on the folklore of the southwest and on desert spirituality while their trips to Iceland remained a “someday, maybe” fantasy. Someday arrived this year.

This was Robert Wilhelm’s seventh trip to Iceland. Past seminars have focused on Icelandic and nordic storytelling in general, but Robert had always wanted to lead a seminar on Njal’s Saga. He knew that such a specialized theme would result in a very small group, which was even smaller, because Kelly, who was teaching, couldn’t come.

Imagine a small group of lovers of myth and folklore, staying in a comfortable guesthouse with great food and lots of coffee, meeting to discuss a unique, 700 year old piece of literature, and then touring places where the events took place. If that kind of travel appeals, check out the Wilhelm’s website. In the first half of 2013, they are planning story-related trips to Hawaii, Arizona, the Orkneys, and Iceland again in May.

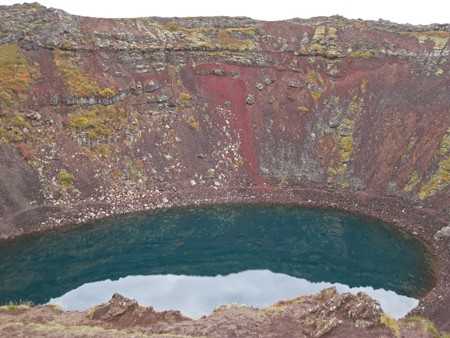

I tried to show some of the visual richness of Iceland in previous posts. Now it’s time to focus on the saga.

***

The Icelandic word for saga means both “story” and “history.” Forty Icelandic sagas are known, and Njal’s is the longest and most popular. The events took place roughly between 970 and 1020 and were written down in the 13th century. Njal’s Saga brings The Illiad to mind, but unlike the epic poetry of the ancient world, Icelandic sagas were literary creations from the start. Single authors gathered the threads of shorter stories and oral histories and wove them into something new. The sagas were read to an audience from manuscripts that were prize possessions of certain well to do families. Nineteen early copies of Njal survive.

Several features resulting from the sagas’ origin and intention can surprise a 21st century reader. Nail biting action adventure scenes are mixed with long genealogies and descriptions of who sat where at a certain banquet. There are far too many characters and subplots for a contemporary novel.

The 13th century, when the sagas were created, was a period of strife for Iceland, with pitched battles that only ceased when the country submitted to Norwegian rule. The sagas were written, in part, to affirm the Icelanders’ personal and national identities. Many living then could trace their origin back to one of the first 400 settlers, so detailed accounts of the doings of their ancestors were always of great interest, in a way that won’t be clear to us at first.

Winter is the traditional time for stories, and in the depth of winter, southern Iceland gets only four hours of daylight. In the northern part of the country, it’s three. In the times described in the sagas, families and friends would gather to spend the winter together. It’s not hard to imagine a dark hall, with people huddled around the charcoal fires, following the reader’s voice into another world, and as the narratives pace became familiar, I found myself settling into the story and understanding why Tolkien borrowed from the sagas in his creation of Middle Earth.

Here is what Robert Cook, translator of the Penguin edition, says in his introduction:

“In Njal’s Saga we read of battles on land and sea, failed marriages, divided allegiances, struggles for power, sexual gibes, malicious backbiting, revenge, counter-revenge, complex legal processes and peace settlements that fail to bring peace, not to mention dreams, portents, prophecies, a witch-ride and valkyries. Behind all this richness lies a well-crafted story of decent men and women struggling unsuccessfully to control a tragic force propelled by persons of lesser stature but greater ill-will.”

Next: The characters, the structure, and the events of Njal’s Saga