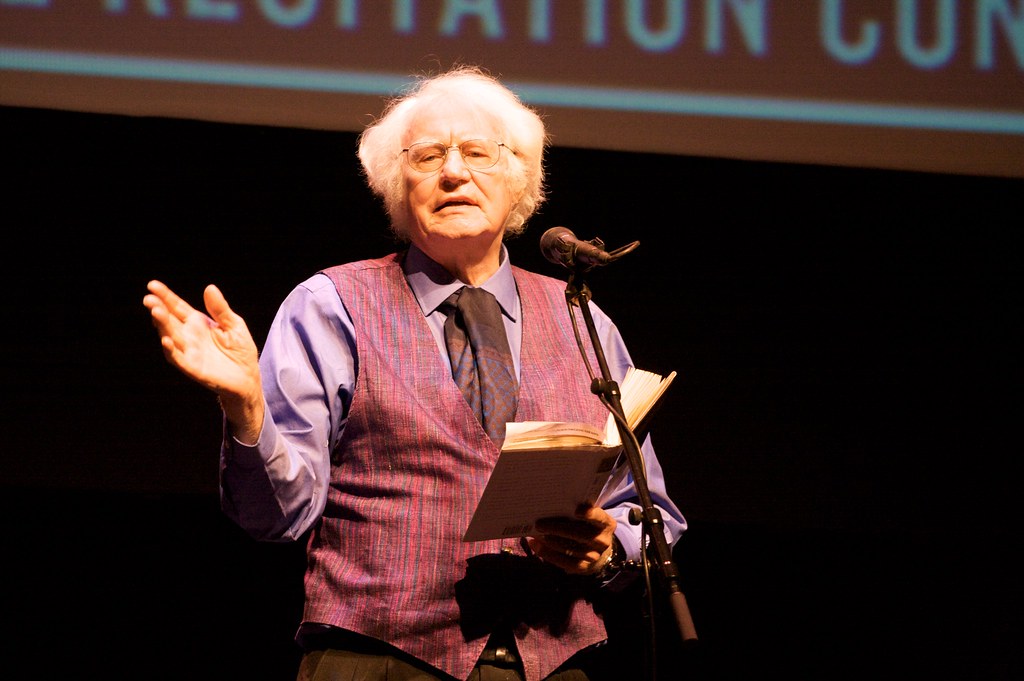

William Stafford, from the announcement of the centennial celebration of his birth, 2014, at Lewis and Clark College

Some poems are prophetic, though readers and the poet alike discover this only after the passage of time. William Stafford (1914-1993) wrote poems like this. Of his process, he said, “It’s like fishing,” and “A writer is not so much someone who has something to say as he is someone who has found a process that will bring about new things he would not have thought of if he had not started to say them.” (1)

Stafford was born and raised in Kansas. During WWII, as a contentious objector, he served in Civilian Public Service camps from 1942 t0 1946 for $2.50 a month. In 1947, he moved to Oregon to teach at Lewis and Clark College, a post he held for 30 years. He was a late bloomer, who did not publish the first of his 57 volumes of poetry until he was 46.

William Stafford was named “Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress” in 1970, a position now called Poet Laureate of the US. He was Poet Laureate of Oregon from 1975-1990. James Dickey said William Stafford was one of those poets”who pour out rivers of ink, all on good poems.” He wrote 22,000 of these in his lifetime, and published 3,000 of those.

He left an unfinished poem, “Are You Mr. William Stafford?” on August 28, 1993, the day he died of a heart attack, containing these lines:

“You can’t tell when strange things with meaning

will happen. I’m [still] here writing it down

just the way it was. “You don’t have to

prove anything,” my mother said. “Just be ready

for what God sends.” I listened and put my hand

out in the sun again. It was all easy.”

In an article in the New York Times Review of Books, Ralph J. Mills Jr. said, “Stafford’s work and attitudes say a good deal indirectly about contemporary modes of living that have lost touch with the earth and what it has to teach. He uncovers and keeps alive strata of experience and knowledge that his readers are in grave danger of losing, and without which, Stafford keeps saying, they will forget how ‘To walk anywhere in the world, to live / now, to speak, to breathe a harmless / breath.'”(1)

All these are reasons why Stafford’s work remains fresh, and seems even more timely as time goes on. One of my favorite poems, “A Ritual to Read to Each Other,” was published in 1962. It seems to me that out of time, he is speaking to us directly, urgently, pointedly at this solstice season of 2016:

A Ritual to Read to Each Other

If you don’t know the kind of person I am

and I don’t know the kind of person you are

a pattern that others made may prevail in the world

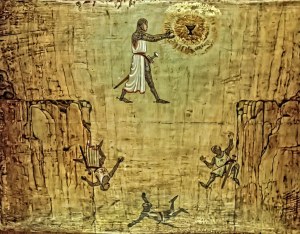

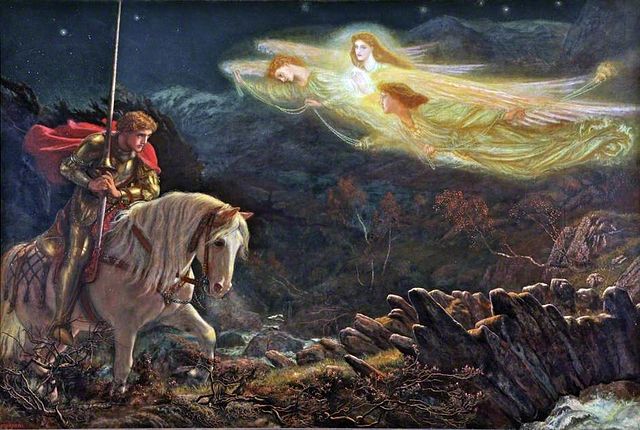

and following the wrong god home we may miss our star.

For there is many a small betrayal in the mind,

a shrug that lets the fragile sequence break

sending with shouts the horrible errors of childhood

storming out to play through the broken dyke.

And as elephants parade holding each elephant’s tail,

but if one wanders the circus won’t find the park,

I call it cruel and maybe the root of all cruelty

to know what occurs but not recognize the fact.

And so I appeal to a voice, to something shadowy,

a remote important region in all who talk:

though we could fool each other, we should consider–

lest the parade of our mutual life get lost in the dark.

For it is important that awake people be awake,

or a breaking line may discourage them back to sleep;

the signals we give–yes or no, or maybe–

should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.

–William Stafford, (from The Way It Is: New & Selected Poems)