In my previous post, I wrote of advances in the field of virtual reality, and posted a video clip that brought to mind the dystopian landscape of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New Word (1932). Huxley imagined life in “The World State” in 2540, where children are born in “hatcheries.” They are raised in “conditioning centers” and learn to be avid consumers and abhor the thought of solitude.

One of the World State’s tools for keeping people docile are “the feelies,” multi-sensory movies, most often centered on sex. The connection to virtual reality should be obvious. Another conditioning tool was “soma,” a side-effect free hallucinogenic drug that World State citizens used to go on “holidays.” Soma relates to the subject of this post – a potential advance in the technology of feeling happy, happy.

In “Unwanted Memories Erased in Experiment,” an article in The Wall Street Journal (12/23/13, p. A1), Gautam Naik writes that scientists used electrical currents to erase memories they had implanted earlier. Someday doctors may be able to zap painful memories and leave the rest in tact. Assuming the technology becomes (relatively) safe, would this be a wise thing to do?

In a few cases it might be – the 39 patients who volunteered for the experiment were already undergoing electroshock therapy for severe clinical depression after all other treatments had failed. But the article’s assertion that memory erasing might be useful to remove “associations linked to smoking, drug-taking, or emotional trauma” suggests the kind of social engineering Huxley wrote about.

Last year at a Buddhist teaching, I met an elderly woman who had spent her youth in a Soviet gulag. As difficult as the hardship was, she had written a memoir for her family to read, “So they’ll know who I really am.” Her core identity, as well as her later practice of Buddhism were direct results of those years of suffering.

In my late 20’s, I knew a woman who lost her closest male friends over a short period of time; they died of cancers related to Agent Orange exposure in Vietnam. After surviving a deep depression, my friend enrolled for training to work in a hospice. Without the pain of loss, she wouldn’t have found her calling.

The poet, Rilke, declined Jung’s offer of therapy work saying, “If you take away my devils, I fear my angels might flee.”

The disowned parts of ourselves are especially important in scripture. When Jesus offers living water (Jn 4:10-13), only those who know they are thirsty will hear him. When Buddha teaches a path beyond suffering, we won’t listen if we’ve deadened ourselves with soma or reality TV.

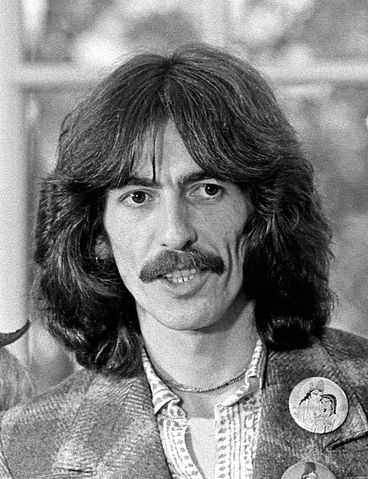

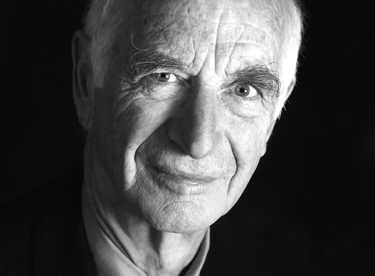

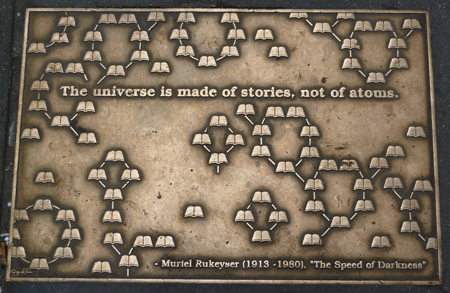

A tour of America 80 years ago sparked Huxley’s vision of an economic and political culture at war with soul values. Now that another “holiday season” has run its course, as the media waits for the next distraction, I am reminded once again of the cautionary words in this wonderful poem that William Stafford published in 1960:

A Ritual to Read to Each Other

If you don’t know the kind of person I am

and I don’t know the kind of person you are

a pattern that others made may prevail in the world

and following the wrong god home we may miss our star.

For there is many a small betrayal in the mind,

a shrug that lets the fragile sequence break

sending with shouts the horrible errors of childhood

storming out to play through the broken dyke.

And as elephants parade holding each elephant’s tail,

but if one wanders the circus won’t find the park,

I call it cruel and maybe the root of all cruelty

to know what occurs but not recognize the fact.

And so I appeal to a voice, to something shadowy,

a remote important region in all who talk:

though we could fool each other, we should consider–

lest the parade of our mutual life get lost in the dark.

For it is important that awake people be awake,

or a breaking line may discourage them back to sleep;

the signals we give–yes or no, or maybe–

should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.