He was just arrested on Tuesday, but already they’re writing ballads about the North Pond Hermit:

Nobody seen his face in twenty-seven years,

Since that day in ’86 when he up and disappeared.

The story has travelled around the world, and unless you are living in the woods, you’ve heard the rudiments of Christopher Knight’s story:

At the age of 19, he disappeared and set up a camp in the woods near Rome, Maine, where he lived for 27 years by stealing sleeping bags, food, propane, and books from nearby vacation cabins and a summer camp. He spent the long winters wrapped in multiple sleeping bags and never made a campfire for fear of being discovered. He spent his time reading and meditating. His only conversation in 27 years was a greeting exchanged with a hiker he met on the trail in the ’90’s.

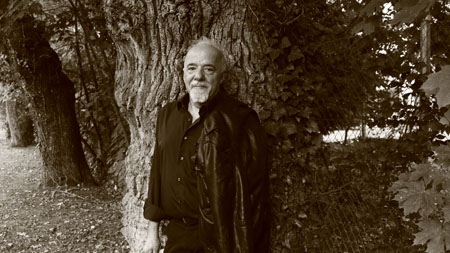

Christopher Knight

When he was arrested, Knight was neatly groomed and clean shaven. He’s up on current affairs thanks to a transistor radio he used to listen to rock music, news, and Rush Limbaugh. That’s about all we know, since Knight politely refuses to talk to journalists or explain himself to anyone. This guy is going to pass on his 15 minutes of fame, his shot at a spot on Letterman, and the chance for a best selling ghost-written bio!

He walked away into the pines to live out in the woods

He turned his back on everything and he was gone for good.

I think the story resonates so deeply because part of us too, wants to walk away from all that crap. “Lives of quiet desperation” in the words of Thoreau, who lived for two years in relative solitude at Walden Pond, but never made or intended to make a break as complete as that of Christopher Knight.

Into an unimaginable mystery like this, each of us will project our own biases. For me, Knight’s practice of meditation aligns him with spiritual seekers who have sought out caves of one sort of another for millennia, but they never threw off all human connections.

Christians have maintained a hermit tradition from the desert fathers through Thomas Merton, but none of them relinquished all human company. Milarepa, a famous Tibetan yogi, lived in a cave for years eating boiled nettles, which gave his skin a greenish cast, yet once he attained awakening, he returned to teach what he’d learned to others.

Did Christopher Knight intend to return someday, to tell us what he’d discovered about the mushrooms and eagles who were his only companions? We don’t know and won’t unless he decides to tell us. In a way, I hope he doesn’t. Whatever his story may be, it will be trivialized and forgotten a week after the tabloids get ahold of it. I don’t want Christopher Knight’s tale to be forgotten.

Some of his old friends have said he was “intelligent, quiet, and nerdy” in high school – just like millions of us, in other words. What could make an intelligent man who is one of us, simply decide to walk away, to opt out? I hope we will wonder about that for a long, long time.

The North Pond Hermit, livin’ in the woods,

The North Pond Hermit, they’d catch him if they could.

You can listen to The North Pond Hermit Song here.

*** UPDATE after posting the original article ***

Troy Bennet and his dog, Hook, who brought you this great ballad, have posted a link to an MP3 version we can download for an optional contribution via Paypal. Bennet says it isn’t his very best song, but it’s the one he’s written about a hermit this week.