“What is the single greatest predictor of a hero’s success in folktales around the world?”

A professor who had studied the subject at length once posed that question in a psychology class. The answer, he said, was finding an animal helper. More than any other human or supernatural guide, an animal ally can lead the hero or heroine through trials and dangers to the end of their quest.

The professor was a friend and colleague of James Hillman (1926-2011) who loved animals and began collecting animal dreams in 1956. Toward the end of his life, Hillman helped compile and update five decades of essays and lecture transcripts for a ten volume collection of his work. Five volumes have been published to date, including Animal Presences, 2012, which I am currently reading.

After serving in the US Navy, Hillman studied at the Sorbonne, at Trinity College, Dublin, and in Zurich, where he received a PhD from the University of Zurich and an analyst’s diploma from the C.G. Jung Institute where he served as Director of Studies until 1969. Versed in Jungian psychology, he charted his own path which he named “Archetypal Psychology.” His first major work, Revisioning Psychology, 1975, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

With 18 volumes in Jung’s Collected Works, and 10 in Hillman’s, it is clearly beyond the scope of a blog post to compare and contrast these two complex approaches to the depth psychology. That said, several broad generalizations are possible:

Jung’s psychology can be characterized as “monotheistic,” aiming at a realization of the “Self,” as the supreme archetypal principle. Jung understood the Self as “the God image within.” Hillman, by contrast, called the psyche “polytheistic,” and considered the Self as simply one of many psychic centers within us. Our nature, as we experience it moment by moment, is more like a pantheon of many gods than the kingdom of single inner supreme being.

As a corollary to these differing models of the psyche, development for Jung was often imagined as an ascent, a kind of upward climb toward spiritual clarity. For Hillman, growth was often a descent, leading to contact with the “Soul,” which for him was more like the “soul” of a blues musician or an artist than the “immortal soul” of organized religion.

Hillman was also concerned with anima mundi, the soul of the world. How can people be healthy when the world is ailing? Hillman had little patience with ego psychologies that pretend human health is possible when our cities are blighted and we work in sterile, windowless offices bathed in florescent light? As a result, his method of approaching dream and fantasy was unique. He shunned methodologies that seek to aggrandize ego by asking what the figures of dream mean. He insisted we treat the beings who visit us nightly with the same courtesy we would show to a guest in the waking world.

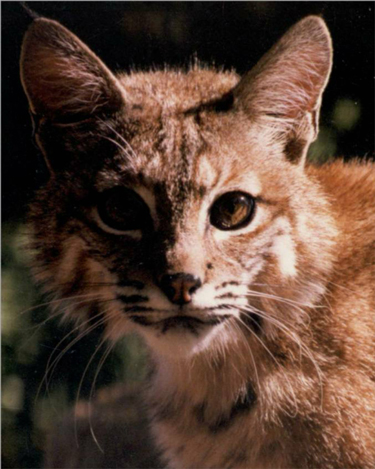

“the animals are right here. You have to be careful you don’t say something stupid because the animals are listening. You can’t interpret them; you can’t symbolize them; you can’t do something that is only human about them.”

“the image is the teacher. We have to endure a laboriously slow method of dreamwork…A dream brings with it a terrible urge for understanding. We want dreams decoded for their meanings. But the dream, like the animal in it, is a living phenomenon. It goes on displaying itself, pointing beyond itself to ever further interiority if we can hold back the hermeneutical desire so that the image can elaborate itself.”

“I am suggesting that the dream animal can be amplified as much by a visit to the zoo as by a symbol dictionary.”

Something within us mourns the animals missing from our lives. We wear their pictures on t-shirts and sometimes collect little animal figurines. We cherish domestic pets in ways that might seem bizarre to earlier generations who weren’t as estranged from the natural world. We thrill at the sight of Coyote or Deer moving through twilight woods at the edge of the housing tract, and we mourn them dead on the road as we drive to work.

We are energized when animals visit our dreams – sometimes. We’d rather they weren’t fierce, threatening, or slimy. We prefer majestic and noble: an eagle, a dolphin, or wolf will do nicely. We’re not so fond of ants or mice, pigs or slugs, skunks or rats.

With the natural world in tatters, however, anima mundi is not dreaming of Disney creatures and love and light. That’s all right. Black Elk said the Lakota people knew every being has it’s place in the medicine wheel. And if we don’t know what’s broken in ourselves and in the world, said Hillman, we don’t have the slightest idea of who and what and where we are.

What animals have recently come to your dreams? What did they seem to want? Don’t remember any animal dreams? Just ask. If you mean it, if you are truly interested and repeat the suggestion until it brings results; if you prime the pump by leaving a notebook and pen you your bed stand, the creatures will visit.

They want to be heard and are looking for those who will listen.